Among the questions regularly asked of journalists are these: Where do you get your stories from? How do stories happen? How do you know a story is a story? And, inevitably, do you make stories up?

Given that there is no single, straightforward answer to any of them, especially that contentious last one, I came across an interesting case last week that helps to cast some light on the process – perhaps I should say, mystery – of story-getting.

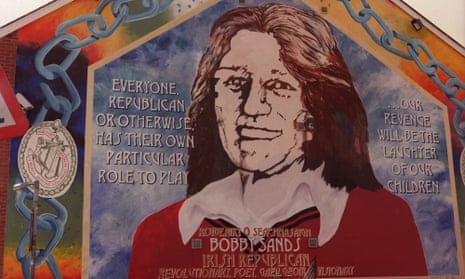

A Belfast-based BBC reporter, Chris Lindsay, was casually reading a guidebook on a Singapore Airlines flight when he came across an item about the murals in the city where he works. These political wall paintings, reputed to number 300, have earned themselves a Wikipedia entry which describes them as symbols of Northern Ireland and points to the thematic differences between those in republican areas and in loyalist areas.

But Lindsay thought the airline guide writer went much further by overstating those differences in rather colourful language. He or she contended that loyalist murals “resemble war comics without the humour” while the republican ones “often aspire to the heights of Sistine Chapel-lite”.

The guide said: “Recently, Protestant murals have taken on a grimmer air and typical subjects include wall-eyed paramilitaries perpetually standing firm against increasing liberalism, nationalism and all the other -isms Protestants see eroding their stern, bible-driven way of life.”

By contrast, murals in nationalist areas featured “themes of freedom from oppression, and a rising nationalist confidence that romantically and surreally mix and match images from the Book of Kells, the Celtic mist mock-heroic posters of the Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick, assorted phoenixes rising from the ashes and revolutionaries clad in splendidly idiosyncratic sombreros and bandanas from ideological battlegrounds in Mexico and South America”.

So, once he landed, Lindsay called a couple of “experts” to ask what they thought of the comments. Was the differentiation fair?

First up was Professor Peter Shirlow, head of Irish studies at the University of Liverpool. He was unequivocal in his assessment, telling Lindsay: “I found some of the commentary to be offensive, if not sectarian. It plays upon sectarian myths of identity and culture in Northern Ireland.” It was unbalanced and unfair.

Next, Lindsay turned to the author Fionnuala O Connor. She told him the comments had a “republican triumphalist ring” while being “patronising and sneering at loyalists”.

Lindsay discovered that the ultimate publisher of the remarks was Fodor’s, the US-based travel guide company. He told them what Shirlow and O Connor had said, and was astounded when, within hours, Fodor’s announced that the section on the murals had been taken down from its website and would also be removed from the next print edition of Fodor’s Essential Ireland.

As far as Lindsay and his BBC editors were concerned they had a story, which duly appeared on the corporation’s news website: “Fodor’s Travel removes ‘offensive’ Belfast murals guide.” The article quickly generated a wider media reaction. The Belfast Telegraph carried a news story in which a loyalist spokesman was quoted as condemning the guide’s comments as sectarian.

Then, just as night follows day, the commentators arrived on the scene. Malachi O’Doherty weighed in with a Belfast Telegraph piece decrying the guide writer’s comments on the basis that “they repeat an old trope that Protestants are dull-witted, while Catholics are vibrant and imaginative”.

In the Irish News, the largest-selling daily serving Northern Ireland, Brian Feeney registered disbelief that this amounted to a story of any consequence because it was blindingly obvious that murals across the religious/political divide are different in tone and content. He was waspish about the story’s genesis, referring to the “predictable” outrage from loyalists “partly engineered by local BBC”. As far as he was concerned, “the people who complained about Fodor’s accurate description of grim loyalist murals with ‘wall-eyed paramilitaries’ are in denial about the state of their own communities.”

Then Newton Emerson, a unionist commentator who has a weekly column in the Dublin-based Irish Times, took the opportunity to denounce the muralists from both communities, arguing that it was time for all the paintings to be erased on the grounds that they lack artistic merit. Maybe, but that’s somewhat beside the point. The substantive issue is that the story, because of Fodor’s extraordinary decision to respond so surprisingly and dramatically to the BBC’s call from Lindsay, had taken off. So why did Fodor’s indulge in what amounts to self-censorship?

Its editorial director, Douglas Stallings, responded to my inquiry with a mixture of doublespeak, corporate defensiveness and one important fact, namely that “the description of the murals has appeared in the print edition of Fodor’s Essential Ireland through several editions with no complaints”.

Here’s the doublespeak. “We did not receive a direct complaint from the person who was offended by our description of the murals … The concerns about the material in question were brought to our attention … via an inquiry from Chris Lindsay.” So, an international publisher decided to delete an item from a guide book because of a single call from reporter who cited “concerns” canvassed from two critics.

And now for the corporate self-justification: “Fodor’s Travel always asks our writers and editors to be aware of potential political and cultural bias in our coverage of any destination. We will ask our writer to review and, if necessary, rewrite the murals feature, and plan to restore coverage of the murals next year when we publish a new edition of Fodor’s Essential Ireland.”

When it comes to doublespeak, however, the response to my queries about the matter by BBC Ulster takes some beating. The opening sentence of its statement was a masterly piece of sophistry: “When the Fodor’s description of Belfast’s murals was brought to our attention, we asked experts and commentators if they believed it was accurate.”

Brought to our attention? It was a BBC reporter who generated that attention. Experts and commentators plural? It was one academic and one commentator.

The spokesperson, in an attempt to suggest an even-handedness that was entirely missing from its online article, added: “We also discussed the topic on some of our radio programmes where a broad range of opinion was sought, including those who believe the Fodor’s account is fair and accurate.”

As has been said of journalism so often, there is a world of difference between “a story” and the truth.

To say there is no difference between the murals in each community is simply to deny reality. Between them, the BBC and Fodor’s have fomented a storm without any merit.