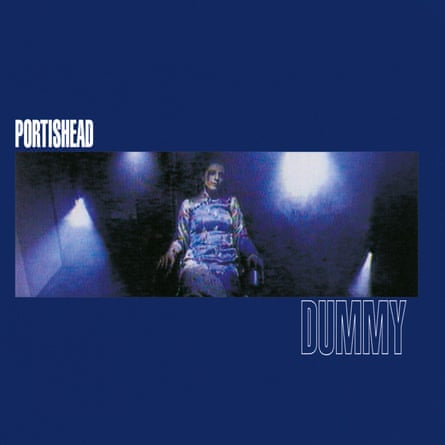

Twenty-five years ago, during the summer of Blur’s Parklife and Oasis’s Definitely Maybe, a darker, stranger record was released that would soon become huge. Its title and mood was inspired by a 1970s TV drama of the same name, about a young deaf woman in Yorkshire who becomes a prostitute. The lyrics spoke of emotional extremes, sung in an extraordinary, rural-tinged, English blues by the Devon-born Beth Gibbons, of “the blackness, the darkness, forever” in Wandering Star, or of the feeling that “nobody loves me, it’s true, not like you do” in Sour Times.

Its sound, woven together by Geoff Barrow and Adrian Utley, helped define what is known today in music as hauntology, the sampling of older, spectral sounds to evoke deeper cultural memories (Boards of Canada’s TV-sampling electronica, Burial’s dubstep, and the Ghost Box label’s folk horror soundworlds would follow their lead). But despite its starkness, Dummy became a triple-platinum seller and a Mercury prizewinner, perhaps because it struck a nerve in what Barrow calls our “sonic unconscious… when sounds can merge with other sounds from somewhere else, and ultimately create emotion”.

It’s a muggy, windy afternoon in a canalside corner of Bristol, the city where Portishead have been making music on and off since 1991. Barrow and Utley are in the studio of Barrow’s record label, Invada, scuttling around drinking coffee and fiddling with a new synthesiser. Despite there being 15 years between them, they have a funny, sweary, fraternal camaraderie. Beth Gibbons is not here, as usual, despite requests: only two short interviews in the mid-1990s revealed the chattier person behind her mysterious persona. (She didn’t do interviews either for her racked, bruising interpretation of Górecki’s Third Symphony with the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, released earlier this year.)

With no reissue to support Dummy’s silver anniversary (a remaster was released in 2014), one wonders initially why we’re here. The trio haven’t released an album since 2008 (the abrasive, career-high Third) or played live since 2015; their last outing, in 2016, was a startling, bleak cover of Abba’s SOS for the film High Rise. But as the two hours unfurl, it’s obvious that this is Portishead’s opportunity to settle scores, to present what Dummy really was. There are also hints that the Portishead story isn’t quite finished yet. As we’re settling down, they talk about needing to speak to Beth to get photos together “for something”, but my nosy inquiries are quickly brushed aside.

When the two men met, Barrow was a ponytailed 19-year-old making demos with the 26-year-old Gibbons at the city’s Coach House Studios (Barrow and Gibbons had met at an Enterprise Allowance training day at the dole office in 1990: “She was a grown-up in my eyes,” he says). Utley was 34, a bored jazz session guitarist finishing yet another job in a room downstairs. “And I remember somebody opening the door upstairs and me hearing It Could Be Sweet [one of the first tracks written for Dummy]. I was all, ‘Fuck me, what is that?’ Just hearing the sub-bass and Beth’s voice – it was unbelievable. Like a whole new world that was really exciting and vital.”

The three bonded quickly. Utley mined Barrow for his knowledge of sampling (“Tell me everything! How are they making that Queen track go on and off?”), while Utley’s collection of TV-recorded spy films introduced his bandmates to unusual sounds from instruments such as cimbaloms and theremins. “It was a really exciting time, because there was this amalgamation of ideas and a lifetime of separate discovery with all of us. And the fact that we brought it to each other…” Utley beams. “It was like a new love.”

Barrow and Gibbons’s first ideas for songs had been recorded in Neneh Cherry’s kitchen in London (Barrow had been hired by Cherry’s husband and manager, Cameron McVey, to work on her second album, Homebrew, on which he co-wrote and co-produced the song Somedays; McVey spotted Barrow’s talent when he worked as a trainee tape operator on Massive Attack’s groundbreaking 1991 album Blue Lines). That working relationship had fallen apart. Barrow’s mental health had also declined. “I was in a terrible place. Through the Gulf war, I was really quite sick, physically and mentally. Mental stuff. I thought the war was the end of the world. I’d never had a breakdown before – I think it was just the pressure of the Portishead stuff – I didn’t know I was having it. And no one ever talked to me about mental health in any way.” “You’re able to hide mental health issues within the music industry,” Utley chips in. “It’s completely acceptable to be a little bit crazy, drink too much or take too many drugs. It’s like: ‘Yeah, man, he was fucked last night’. No one asks, ‘why was he fucked?’ I think that ignorance has been going on for ever.”

Dummy motored on after Portishead, now a trio, moved to the Bristol district of Easton to record. “That was grim too,” Barrow laughs. “The only place to eat was Iceland or this horrible pub called Granny’s where your beans and chips would arrive with Granny’s thumb in it.” The lush soundscapes of Dummy rose from that bleakness. “But the process is never romantic, is it?” Barrow continues. “Listen to how New Order made their first records, or whoever, and it’s always going to be the same story. You’re in some shithole somewhere that you’ve made into something OK.”

Bristol has changed since then, but not in a good way, the men say. Homelessness and drugs problems are even bigger issues. “Plus you go somewhere like St Pauls – which was very much a community of Caribbean people – and there’s some posh student in a onesie,” Utley says. “Really privileged kids that have taken that area over.” In 2017, Bristol was named the most desirable British city to live in by one survey, but also the most racially segregated by another. Its past has always been unpleasantly divided, says Barrow, citing a book called A Darker History of Bristol, which recounts its history with slavery. “And still, lots of Bristol people only give a fuck about themselves,” he adds. “But there’s been an anti-establishment arts scene here too, for years, with a massive tongue in its cheek. It was there in the Pop Group, Smith and Mighty, the Wild Bunch, and Banksy [Barrow was music supervisor for Banksy’s 2010 exhibition, Exit Through the Gift Shop]. It’s always found itself.” A note of hope, then? He shrugs, still unsure.

Portishead have always been a political band on their own terms. A quote from Jo Cox (“We have far more in common than that which divides us”) was featured in their 2016 video for SOS; it still sits on their website’s landing page. Barrow and Utley also rant about Brexit, Trump and the Tories on Twitter feeds constantly; we meet four days after the new PM arrives, which Barrow calls “an absolute fucking disaster” (he later retweets Jeremy Corbyn’s plan to stop a no-deal Brexit).

Utley also mentions Gibbons’s lyrics being “very visceral and political” about gender and the politics of relationships, despite their abstract nature. He recalls Gibbons pointed out a “mansplaining” incident in a restaurant, and it reflecting one of her songs (they don’t mention the song, adding they don’t discuss her lyrics in detail). Barrow also recalls sexist record company A&Rs from their early days. “This real meat and veg vibe. Men going: ‘What’s this moaning bird on about?’”

By winter 1994, Dummy was everywhere. And in January it went to No 3 in the charts, behind Celine Dion and the Beautiful South. Sour Times and Glory Box became top 15 singles. Then came the Mercury win, at which Barrow ranted about prizes being preposterous (“I still agree with that”). He also recalls his mum being cross with Paul Morley (“he’d dissed us a bit”) and chatting amiably to Noel Gallagher. “I remember thinking, Oh, most musicians are dead normal. Or at least as mad as you.”

Barrow and Utley’s main beef is that Dummy is remembered as a sexy, chillout record in the UK. “When people say that, I find it bizarre.” He says Portishead had far more in common with Nirvana than any dance or chillout acts. “I know that sounds ridiculous – but they also had these visceral chord changes, never being harmonically correct.” He has a theory though: that the dance culture that happened in Britain didn’t happen elsewhere on the same scale, “so when everyone was partying and taking pills and coming down, the attitudes were different.” Portishead are just seen as a vocal-led band elsewhere, he adds, with Gibbons as a Polly Harvey or Hope Sandoval figure. They’re huge in France, Switzerland and the US, where Third entered the charts at No 7, and in Latin America: they played to 80,000 in Mexico City. Despite their recent silence, every Portishead musician remains busy. Barrow makes film scores with composer Ben Salisbury (his latest for the Octavia Spencer and Naomi Watts film Luce, is released in the UK this November) and “really loves” playing live with his Krautrock-influenced band Beak. Utley has made a soundtrack with artist Gillian Wearing for a George Eliot documentary recently, worked on Anna Calvi’s latest LP, and with the Paraorchestra of Great Britain on several projects.

They’re still passionate about new music. Both fathers, they like “that great gothy woman the kids like who makes stuff on Logic on her laptop” (we work out it’s Billie Eilish), James Holden, Idles, Hildur Guðnadóttir and Sharon Van Etten (Barrow), Kate Tempest, Thurston Moore and Perfume Genius (Utley). Things they don’t like include composer Nils Frahm, about whom they rant for five hilarious minutes. Barrow: “He’ll change his scarf half way through to prove how important he is.” Utley: “He’s grade 3 piano. He’s fucking Richard Clayderman.”

That joyous railing against everyone else, that sticking to one’s guns, makes you wish for Portishead to return as a musical entity even sooner. Utley confirms he was the last to see Gibbons: “The other week for lunch. It was great. We slagged everything off!” Will we see them back together soon? The men look at each other for a moment too long – moments later, as I start to leave, they’re talking about the photographs again. “It’s all up in the air, really,” Utley says. “If the wind blows hard enough, you never know.”

As I leave, a gale outside roars. Darker, stranger things keep on happening.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion