Twelve years ago, Sheryl Crow was laughed at for suggesting that green-minded people should use only a single square of toilet paper every time they go to the loo (or two to three sheets for “pesky situations”). Well, we’re not laughing now, are we?

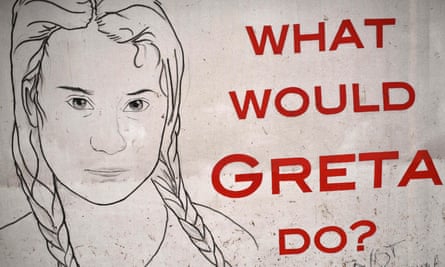

On the day before the hottest day of the year so far (temperatures at Glastonbury hit 30C, elsewhere in the UK 35C), Crow knocks out hit after hit on the Pyramid stage under a giant globe, Glastonbury’s reminder that we’ve only got one planet, and dedicates Soak Up the Sun to Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old Swedish environmental activist and school striker. Thunberg’s spirit is embedded in Worthy Farm this year. There are murals of her face with the slogan: “What would Greta do?”

But another environmental legend makes it in person. David Attenborough, a surprise addition, comes out to enormous cheers from the massive crowd in front of the Pyramid stage – possibly the loudest of the entire festival. Giving a shoutout to Glastonbury for going plastic-free, he then introduces a little treat – a trailer for his next show, One Planet: Seven Worlds.

This year’s festival has been sold as Glastonbury’s greenest ever. As Attenborough mentions, there has been a much-publicised ban on single-use plastic on site (although actually this is just a ban on vendors giving out single-use plastic; punters are allowed to bring in plastic bottles, but encouraged to reuse them at 850 refill points).

At the last festival, in 2017, visitors used 1.3m plastic bottles, and the clean-up operation cost almost £800,000 and took six weeks – despite perennial pleas from Emily and Michael Eavis to “Love Worthy Farm, Leave No Trace”. Festivalgoers have been informed that leaving tent pegs in the ground could result in cows eating them and dying.

Despite the 15,000 colour-coded bins, the site is still a sea of detritus. But nobody I speak to admits to having discarded, say, the Calvin Klein underpants I spot on the ground while queueing for ice-cream. (The ice-cream vans, of course, idle all day long, exhaust fumes mixing with the dust kicked up by thousands of marching feet. A lot of the stewards pair their fluorescent jackets with face masks.)

There is excitement around Extinction Rebellion’s appearance on the Park stage on Thursday. Friends Harry Hayward and Minnie Bartley (both 22) and Joe Holley (23) are sitting in the park eating pizza, Harry in a multi-coloured umbrella hat (“It’s quite sweaty”). It’s their first time at Glastonbury. They want to talk about environmentalism and politics (it has been noted that more people yelled: “fuck the government and fuck Boris” at Stormzy’s Saturday headline set than will actually be able to vote for Johnson to be prime minister, while Zac Goldsmith was booed at his own event).

“It’s definitely good that Glastonbury is pushing the green agenda. I’ve been on the last two out of three Extinction Rebellion marches in Leeds,” says Harry. “But we need to do something about this Tory government. Some of the reaction [to the climate demonstrations, to Thunberg’s parliamentary address] has been really negative.”

Minnie has noticed an increase in people caring. “Even in a year, with things like plastic straws. Every little helps.” But Joe outlines the wider problem when he says that, in preparation for Glastonbury, he bought a reusable water bottle from Amazon, “and it came in so much packaging, loads of it”.

The Extinction Rebellion set features Kurukindi, a Kichwa Amazonian shaman. Many in the crowd (some dressed in bee headdresses, or holding placards painted with whales) are visibly moved by his performance.

Speeches by Extinction Rebellion’s co-founder, Gail Bradbrook, and Greenpeace’s Rosie Rogers follow. A huge cheer erupts when Rogers calls the MP Mark Field, who grabbed a Greenpeace protester by the back of the neck before marching her out, a “scumbag”. “The only thing we were armed with were leaflets and peer-reviewed science.”

A procession to the stone circle, ending in people forming a giant human hourglass (because time is running out), is fairly shambolic, but Extinction Rebellion’s pastel pink boat – the one that hosted Emma Thompson in Oxford Circus, and is named after Berta Cáceres, the late Honduran activist – is even prettier in the flesh.

At the Extinction Rebellion base in the Green Fields, Clarissa Carlyon, who has been volunteering with the group since October 2018 and was heavily involved in planning the April occupation, says Glastonbury has been really accommodating to the group. But is it enough, I ask. And doesn’t she think other festivals have been way ahead of the curve? Mandala festival in the Netherlands, or Shambala in Northamptonshire, for instance, which is powered by 100% renewable energy and doesn’t allow Coca-Cola and Nestlé products to be sold on site.

“I think it’s really tough when you have something the size and scale of Glastonbury,” she says. “But they have given us this space, and other spaces, and we’ve got videos playing around. It is great that the festival is embracing what we’re talking about. I do feel it is seeping into the DNA of the place.”

Glastonbury has long been conscious of its footprint. The reusable 80% recycled stainless steel cups sold on site for a fiver were originally produced in 2016 as a way to help support the besieged British steel industry. (Although I watch loads of people being served their drinks in cardboard cups even when they proffer their steel cup, and the cardboard cups do not always end up in the correct bins.)

It is also customary that any tents left behind are repurposed. In 2016, a charity called Aid Box Convoy collected abandoned tents and sent them to refugee camps in Europe. (But it is estimated that 90% of tents left at festivals end up as landfill.)

At a Leftfield event called How to Save Our Planet, the Labour MP Clive Lewis and Minnie Rahman, from the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, point out that climate justice intersects with social, racial and class justice. Rahman says: “White people are overwhelmingly represented in the climate movement. I’d really like to see the movement taking forward the connection that climate change doesn’t affect us all equally. We see people in the global south, for instance, dying to protect their land, or the health impacts in parts of Britain because of air pollution.” A panel by gal-dem makes similar points in their own discussions.

The Leftfield tent is rammed. Although a few brims of straw hats are sliding down noses in the midday heat, the Green party’s Caroline Lucas is afforded a rock-star welcome and a huge cheer goes up when she mentions Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Lucas’s reference to the Green New Deal, a private member’s bill she has tabled with Lewis that is inspired by Ocasio-Cortez, is met with a cacophony of applause. An audience member mooting the role nuclear power might have in addition to renewables is quickly talked down.

The Norwegian singer Aurora released A Different Kind of Human (Step II), an album themed around ecological disaster, earlier this month. Before performing on the John Peel stage, she tells me that she always knew the album was going to be about the climate crisis. When I ask if she will be sticking around after her set, the answer is no, because she is flying to Belgium. What does she do to lessen her own environmental impact, especially when touring? She mentions wooden toothbrushes and being vegetarian.

Johannes Hogebrink, an artist from Amsterdam, has also flown to the UK for Glastonbury and is busy crafting a sand sculpture for Extinction Rebellion. The sculpture is a huge skull with a beetle crawling out of one eye and money coming out of the mouth. “You cannot eat money, oh no!” as Aurora’s song The Seed has it.

Over at the Shangri-La, this year’s theme is “Junkstaposition” and it is home to the Disruption Bureau, a training centre for activists. Organisations including Amnesty International and Extinction Rebellion offer activities such as placard-making and flag-printing, but the most common interactions I observe are the handing out of leaflets and the signing of petitions.

However, there is a great audio installation by Echoic Audio called Memory Tree, and the open-air art pieces are impressive, if not beautiful (that’s kind of the point), including trees that are made from assorted waste. The Gas Tower is made entirely from recovered ocean plastic.

Before her panel, I ask Lucas about Glastonbury 2011, when she appeared on the Pyramid stage before Wu-Tang Clan. “It was great,” she says, “inspiring and exciting. But terrifying.” She is thrilled that young ipeople are taking up the climate cause, such as George Bond, a 16-year-old activist, also on the panel. Equally inspiring at the other end of the age spectrum is Barbara Richardson, here on behalf of the Fracking Nanas.

Bond throws an important date out, 20 September, which he says will be “the largest climate demonstration this country ever has seen. It’s gonna be huge, it’s gonna be beautiful, but it’s also gonna be filled with anger and rage that nothing has been done.”

Last week, the government pledged to get net emissions down to zero by 2050. But it is simply not good enough. As Lucas puts it, it’s a bit like calling the fire brigade in an emergency and asking them to turn up in 30 years’ time.

As the burning sun goes down and jumpers are pulled out from backpacks, a man tosses his chip wrapper on the ground, his mate crushing a can before hurling it into the grass. A bunch of people take cocaine in the gloaming, which in its own way is ravaging the parts of the world Kurikunda talked about protecting.

Glastonbury is making a massive effort, albeit with room for improvement. And the ecstatic response to Attenborough is an indication that environmentalism is much cooler than it ever was – people genuinely care now. But we’ll know soon enough whether the festivalgoers matched the organisers’ green aspirations and took away with them not just brilliant memories, possible sunburn and multiple blisters, but all the other rubbish they were asked politely to do so.