In 1987, Nigel Gilmartin was working as a mobile DJ in Blackburn: weddings, engagements and birthdays at community halls; the shirt-and-tie scene at weekends. That summer, he fell under the spell of the Sunday-night shows on Key 103FM as DJ Stu Allan played early acid house and hip-hop across Greater Manchester and Lancashire. Gilmartin would meticulously note the name of every track and then scour east Lancashire’s record shops with his list. One record shop staffer told him about Tommy Smith, a hippy Glaswegian hedonist who was looking for DJs for a new type of party in Blackburn. The next day, Gilmartin gave him a call.

Blackburn’s venues were uninterested in Smith’s designs on bringing house music to the town until Clitheroe Kate – a key figure in the town’s gay scene around Mincing Lane – rented Smith a room at a bar called Crackers. “You knew something was happening,” says Gilmartin of the first party. “It was absolutely bouncing.” After a few weeks, demand was wildly outstripping Crackers’ capacity. Smith decided to take the parties to the empty mills – relics of Margaret Thatcher’s crushing impact on the former textile town. For Smith, the parties were a vanguard against the prime minister. “She was saying there’s no such thing as society,” he says. “We were saying there is, we’ll show you – here’s 10,000 people. It was political, it was taking them on: people could come together and share collective hopes and aspirations.”

If the Blackburn parties at the end of the 80s are mentioned at all in the annals of rave history, it is as an afterthought to what was going on 30 miles away in Madchester. In reality, Blackburn was one of Europe’s largest, earliest and most innovative scenes. Starting just as Danny Rampling’s London club Shoom was launched in late 1987 – widely viewed as the birth of acid house in Britain – the Blackburn parties would grow to a near weekly event for between 7,000 and 10,000 people. Yet the memory of these nights is largely the preserve of niche Facebook groups and unexpectedly sad YouTube comments: “Best days ever never to be repeated,” says one, followed by a dozen pill emojis.

Only now, 30 years on, is its story being told. Part-funded by Arts Council England and created in response to the 2019 British Textile Biennal, Acid House Flashback is an online archive established to collect oral testimonies, images and ephemera from the Blackburn parties. “This wasn’t art-school criminality,” says Jamie Holman, who co-runs the archive with Alex Zawadzki, artists from Blackburn and Morecambe respectively. “This is really very raw, so it’s been a real challenge. Is Blackburn finally going to make it into the canon?”

In 1987, the loose Hardcore Uproar collective, an unorthodox coalition encompassing hardened football hooligans and crusty free-spirits, formed to organise the scene, holding weekly Monday meetings to share out tasks. The parties were whatever punters wanted them to be. For some, that meant hearing the exhilarating new sounds from Chicago. For others, breaking into buildings seemed like the primary buzz. For Joe Fossard, a sound engineer, it was both. “I classed myself as an audio terrorist,” he says. “Breaking into somewhere, doing the sound – it was a real challenge, a massive responsibility.”

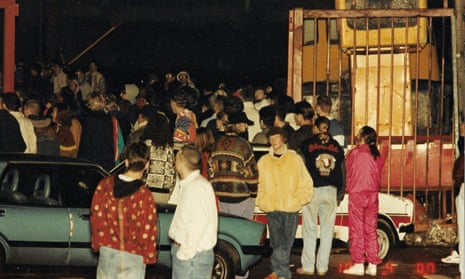

Hardcore Uproar posted very vague flyers around town advertising parties at the Sett End pub on Saturday nights. Ravers would pack into the pub – known locally as the Sweat End, owing to the perspiration that dripped from the ceiling – and, at 2am, form convoys to the secret warehouse locations. There were no bouncers, just the odd football casual in a ski mask. Inside the mills, empty production line floors were repurposed for dancing. Older factories were notoriously rickety. To cover the holes in the roof, remembers Wendy Newsome, who danced at almost all the parties, “they’d stick big sheets up covered with luminous paint”.

The Blackburn crowd loved the squelchy new acid sounds and the optimism and exaltation of booming vocal house. Local DJs such as Gilmartin or DJ Shack were preferred, although there were guests: Sasha first attended as a punter, and later played live. The Lancashire Evening Telegraph soon became aware of the parties, warning of “half-naked girls”, drugs and loud music. This was not the deterrent the paper’s editors had imagined: it functioned as an advert for what would become a broad crowd. “I was expecting these trendy dudes, but it wasn’t like that,” Fossard says. “It was really rootsy, down to earth.”

Blackburn’s mills had been closing throughout the 70s, but the economic shocks of the early 80s made that decline almost total: Lancashire’s unemployment rate was more than double the national average. For Hardcore Uproar, keeping entry cheap was a political issue. Many of the early parties cost just £1 to enter; prices rarely crept above £3. “There was a catchphrase at the time: ‘Can you feel it?’” says Smith, alluding to the Royal House acid war cry. “For us, it was: ‘Can you afford it?’”

Blackburn also offered an alternative to clubbers deterred by the increasing gang presence around the Haçienda. “People were looking for options that didn’t quite have the problems of Manchester,” says Sasha. That the Haçienda finished at 2am also contributed to Blackburn’s appeal. “The Hacienda was pyjamas, man,” says Smith, laughing. “Besides, nightclubs were the enemy.”

If police turned up to shut down a party, Hardcore Uproar would often open the doors and let everyone in for free, letting chaos ensue. Foxing the police was baked into their agenda – later parties were even titled “Revenge”. Multiple decoy vans would set off from the pubs in different directions. Soundsystems were built to be dismantled quickly, with electricity sourced from nearby lampposts. Police tactics to neutralise the acid parties – titled Operation Alkaline – were not working, despite Blackburn MP Jack Straw insisting that the town “is not short of places for young people to go and enjoy themselves”. Fossard remembers his Labour-supporting father leaving a meal with Straw to help deliver a soundsystem to a warehouse party. “He left my mum chatting, then just went back and carried on dinner.”

The collective’s ultimate triumph came in November 1989, with a party at a large warehouse that formed part of the Conservative government’s enterprise zone scheme – designed to provide a space for budding entrepreneurs and industry in low-employment areas. Smith recalls sitting in the building’s upstairs office, watching the winter sun rise over the town. “I had this cosmic moment where I thought: ‘Of course! They’ve done it! Thatcher’s government had gifted us the most beautiful party location.’” Smith even appeared on television, declaring to Tory MP Ken Hind that he was not on drugs or alcohol, simply “high on hope”. The phrase would be quoted by loved-up dancers throughout 1989, encapsulating the moment’s giddy, defiant spirit.

Fanzine publishing flourished (E’ By Gum: Ecstasy in the North being one title) to meet the demand for safe drug guidance, rights advice and wide-eyed proselytising about the DayGlo future to come. “The 90s belong here in Blackburn,” reads one fanzine missive from the end of 1989, “and it is up to each and every one of us to make it happen.”

But within a few months, the parties were over, scuppered by threats from organised crime and the law. Salford gangs took control of the parties. Smith was kidnapped. “They took us to the basement in the Haçienda; it was the first time I’d seen a gun,” he says. “They said: ‘You work for us now.’ They came along and ruined the whole thing. Selling dodgy drugs, smashing buildings up. It was foul.” Piers Sanderson made a still-unreleased film about the parties. “You couldn’t believe that this beautiful, life-changing experience now had this threat of violence,” he says.

The Sett End was closed in 1990 as a mood of anxiety descended regarding police infiltration and surveillance. A party in nearby Nelson, in spring that year, proved climactic. As Candy Flip’s cover of Strawberry Fields Forever reverberated around the mill, a bolt of white light emerged – the shutters had been raised, revealing rows of police with riot shields. “Fear went through the crowd,” says Sanderson. “Everybody tried to run. How somebody didn’t get killed, I don’t know.” Sasha was up in the booth, watching the police stream in. “There was a couple of guys in wheelchairs who’d always be at the parties,” he says. “I remember seeing them knocked out and sprawled across the floor.”

Newsome and her friends tried to hide in the loos. “We were hanging on from the cistern with German shepherds barking at our legs,” she says. Smith saw police horses “lined up on the hill like some sort of John Wayne movie”. Luckily, nobody died in the stampede, but Hardcore Uproar knew they couldn’t guarantee the crowd’s safety should the police repeat the Nelson tactics. There would be no more Blackburn parties. “I expect this to be a clear signal to the organisers of these events,” police told the Lancashire Evening Telegraph, “and we shall now be looking to the courts.”

Smith was arrested on suspicion of supplying class A drugs and held on remand for a year until being found not guilty. “You’re lying in prison in a cell with two other people, everything taken away from you,” he says. He emigrated to India shortly after release.

Dance music became professionalised, but few in Blackburn – now without a club scene – went on that journey. Its story was forgotten. Manchester had charismatic advocates with media platforms able to turn rave into urban regeneration. Blackburn’s young people were just trying to hold down day jobs or keep the DSS off their back. Today, there’s a contemporary debate about who gets to tell dance music history. For Holman and Zawadzki, Flashback is the first step towards recognising the parties for what they were – working-class people staging a cultural intervention, and a political retaliation to a Conservative government that had written Blackburn out of the future. “We wanted to put it in its historical context,” says Holman, “but also, the context of what’s happening now.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion