One day earlier this year, two prison officers led a portly, middle-aged man into court and instructed him to sit in the dock. He was wearing an ill-fitting grey suit and a grey tie; his hair was grey, and so too were his handcuffs. The only flash of colour came from his florid and slightly sagging face. In the public gallery, 10 feet behind the dock, a handful of people sat and stared at the back of the man’s red neck. Outside, 30 armed police officers were standing guard.

In the dock, Gary Haggarty sat and listened for almost an hour and a half as the judge explained the sentence he was about to receive, for offences to which he had already pleaded guilty. It took so long because there were so many crimes to be considered: 201 of them, in fact.

They included five murders; five attempted murders; one count of aiding and abetting murder; 23 conspiracies to murder; four kidnappings; six charges of false imprisonment; a handful of arson attacks, including burning down a pub; five hijackings; 66 offences of possession of firearms and ammunition with intent to endanger life (the weapons included two Sten submachine guns, an Uzi, 12 Taurus pistols and two AK47s); 10 counts of possession of explosives; 18 of wounding with intent and two charges of aggravated burglary. There was also criminal damage: just the one charge, although this covered the destruction of several houses during a six-month period.

But this was not all. There were also a number of TICs, as they are known in UK courts – offences “taken into consideration”. Offenders are allowed to admit TICs as a way of saving the police and the courts time and money, and they are usually minor additional infractions: when someone pleads guilty to shoplifting on four occasions, for example, they may ask the court to consider two further shoplifting offences as TICs.

On this occasion there were 304 additional offences taken into consideration. They included a number of malicious woundings; possession of an array of firearms, including three Bren light machine guns and a number of assault rifles; extorting money from various takeaway restaurants and a pool hall; making “an unwarranted demand of a quantity of fuel” from a petrol station; burning down said petrol station; unlawful imprisonment; 37 assaults; robbery; car theft; possession of amphetamine and cannabis with intent to supply; and possession of various offensive weapons, such as hatchets, baseball bats and a telescopic baton, while in a public place.

The offences were committed between 24 February 1991 and 1 March 2007: a serious crime committed every couple of days for 16 years.

Among the people sitting in the public gallery were relatives of Haggarty’s victims, and some of the judge’s sentencing remarks must have been almost unbearably painful to hear. Haggarty’s first murder victim was Sean McParland, a 55-year-old who was killed while babysitting his four grandchildren, who were aged between three and nine. The nine-year-old gave a statement to police in which he described an armed man busting into the house. As the man took aim, his grandfather “started to bend down and was flapping his arms”. The bullet hit McParland in the left side of his face and severed his spinal cord before exiting the right side of his neck.

Haggarty had told police that he wanted to say sorry. That killing was a case of mistaken identity: the intended victim was McParland’s son-in-law.

Another victim was John Harbinson, 39, who had been handcuffed to railings in an alleyway and beaten to death with a hammer. Haggarty had told police that there had been no intention kill Harbinson – just to hurt him. At the back of the court, Harbinson’s son, Aaron McCone, heard how his father had been left to die after suffering skull fractures, eight broken ribs, two lung punctures, and fractures to one ankle and both wrists.

As the judge wound up, it was clear that most of these 500 crimes had been committed within a few miles of the semi-detached house on the Mount Vernon estate in north Belfast where Haggarty, a 46-year-old former tyre fitter, lived with his wife and son.

Haggarty was a serial killer, sadist, kidnapper, drug dealer, racketeer: a one-man crime tsunami. He was also a member of a Protestant militia, the Ulster Volunteer Force, fighting against the IRA and other Irish republican forces to keep Northern Ireland under British rule. He got away with his crimes for so long because he was, in addition to these things, a servant of the British state. He was a police informer.

Informers became an increasingly powerful weapon in the armoury of the British state during the three decades of Northern Ireland’s Troubles. For the police and the army, informers were a vital source of intelligence about republican and loyalist paramilitaries; they also offered an opportunity to exert a degree of control over these groups.

The history and literature of Ireland had long been crowded with informers, many of them working for the English. In the mid-17th and again in the late 18th centuries, informers working for the crown played a key role in the defeat of major countrywide rebellions, helping to consign future generations of Irish men and women to continuing rule from London.

Once the Troubles erupted in the late 1960s, both the Intelligence corps of the British army and the local police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), began to recruit informers once more. It started as a modest effort: the first suspected informer within the IRA, a young father of two called John Kavanagh, was shot dead by his comrades in January 1971. But in the years that followed, dozens more met the same end: interrogated, sometimes tortured, killed with a shot to the head and their hooded bodies dumped in back alleyways or country lanes.

It is impossible to know how many were recruited over the years, but it seems likely there were hundreds, drawn from Catholic and Protestant communities. The most prized informers were those within the republican groups attempting to force the British out of Northern Ireland, particularly the IRA. But the police and army also recruited paramilitaries who were fighting for the north to remain part of the UK – men such as Haggarty, who was a member of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).

Responsibility for running these informers was divided between Special Branch – the intelligence-gathering detectives of the RUC – and the army’s Intelligence corps units. Sometimes Special Branch and the army co-operated closely; sometimes, it seems, they did not. But all the time, the indistinct shape of MI5 could be sensed, hovering in the background, where it co-ordinated efforts and provided ready cash.

These three organisations would not hesitate to use any means available to recruit an informer: bribes, blackmail and threats to family members, as well as appeals to basic humanity. “But usually they would draw on some moral problem in your past to try to get their hooks into you,” a former IRA man once explained to me.

“A moral problem? You mean, like having killed someone?”

“Oh no,” he laughed. “If you’re a republican, you’d do that and then go home and have your dinner.” He winced. “I mean like being unfaithful to your wife.”

Photograph: Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images

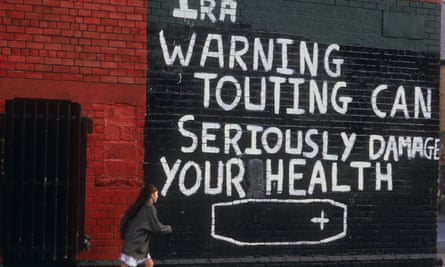

A whole nomenclature sprang up to condemn those on both sides who betrayed their community and their comrades: widemouths, supergrasses, Brussels. For their part, detectives in Northern Ireland would describe paramilitaries such as Haggarty, who appeared to lead a charmed life, as “protected species”. Nowadays the security service officers of MI5, in Northern Ireland and elsewhere, call them “chisses”, from an acronym established by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which has governed the recruitment and running of agents since 2000. The Act describes such individuals as a “covert human intelligence source”, or CHIS. But the preferred term in Ireland has always been “tout”.

In 2007, the police ombudsman for Northern Ireland produced a report that examined the complex relationships between police officers and Haggarty’s UVF in north Belfast, and the role that those relationships played in one particular murder. The ombudsman concluded that there were systemic failings resulting from the way Special Branch officers had protected informers who were suspected of murder and other serious crimes.

The recruitment of informers created moral and legal problems for the British state that are very much alive today, when memories of the conflict remain raw. If a terrorist was put on the British government’s payroll, and allowed to remain at large, sometimes for decades, who then bears responsibility for the acts they planned or carried out? Who decided whether terrorist attacks that were known in advance to the British security services would be allowed to proceed in order to protect that informer? And how high within the various agencies, or in government, were such judgments made?

A decision to place the use of informers at the heart of the British security strategy in Northern Ireland appears to have been taken at the highest levels ofgovernment in 1979, after the security forces endured their greatest setback of the conflict, when the IRA killed a member of the royal family and a large number of British soldiers in separate attacks on the same day.

Shortly before midday on the morning of 27 August, a remote-controlled bomb was detonated aboard a boat off the coast of County Sligo, killing the Queen’s cousin Lord Mountbatten, along with an 83-year-old woman and two boys. The IRA said it wanted to send a message to the English people that it intended to “tear out their sentimental imperialist heart”. A few hours later, 18 soldiers died in an ambush near Warrenpoint in County Down. The IRA had never killed so many troops in one attack: the casualties included a lieutenant colonel, the most senior British officer to die in the Troubles.

The British government was so shocked that Margaret Thatcher persuaded Sir Maurice Oldfield, the former head of MI6, to come out of retirement to co-ordinate security in Northern Ireland. Oldfield, an intelligence officer rather than a policeman, saw the gathering of intelligence as the key to winning the war against the terrorists. But during the next two decades, the bombings and shootings continued, the death toll grew and grew, and more and more informers were recruited. In June 1994, for example, when UVF killers sprayed automatic rifle fire at a group of men watching World Cup football on a pub TV in the tiny village of Loughinisland – killing six and wounding five – it turned out that two of the killers, unknown to each other, were informers.

In 2011, John Stevens, the former Scotland Yard commissioner who conducted three investigations during two decades into allegations of collusion between loyalist paramilitaries and the British state in Northern Ireland, told a parliamentary committee that his team had arrested 210 people, and only three were not working for the police or military intelligence.

Stevens and his team discovered that immediately after Oldfield was appointed, he had recommended that a senior MI5 officer, Patrick Walker, examine police intelligence gathering in the province. Walker, in turn, recommended that the recruitment of agents within the ranks of paramilitary organisations be given priority over the detection of crimes committed by those organisations.

According to an order issued to senior RUC officers in February 1981, detectives from the RUC’s Criminal Investigation Department (CID) who were investigating terrorist attacks would in future be required to consult Special Branch detectives before they arrested anyone. The order – which remained secret for 20 years – explained: “All proposals to effect planned arrests must be cleared with Regional Special Branch to ensure that no agents of either RUC or Army are involved.” In other words, informers were to be protected.

Quietly, with no public announcement, the RUC had been turned from a police force whose priority was detecting crime and putting criminals before the courts, into one whose principal aim was to spy on terrorists.

In time, there were so many touts that an extraordinary new form of literary genre emerged from the conflict: the informer memoir. In the past 20 years, five former touts who were living in witness protection programmes have published books detailing their activities, and some were bestsellers. Despite this, the informer has mostly remained a reviled figure within many communities in Northern Ireland. Traditions of republicanism and loyalism thrive in areas where there are close community networks and extended families; communities where codes of loyalty and sacrifice are handed down from one generation to another. The tout’s acts of betrayal were never merely national or even organisational affairs: they were also deeply personal.

While some loyalists appear to have turned readily to informing – they were, after all, supporters of the British state – they still risked death for betraying their comrades’ activities. Haggarty had been an informer since the early 90s, but in 2010, after he began co-operating with the officers who arrested him for questioning about the murder of John Harbinson, he was spirited away to England. At this point, the UVF sentenced him to death in absentia. In nationalist areas, even those people who abhorred the IRA’s campaign of violence would rarely contemplate giving information to the police. In such areas, being branded a tout was worse than being accused of being a paedophile.

In 2007 a republican paramilitary, Raymond Gilmour, who had published a book, Dead Ground: Infiltrating the IRA, asked publicly for forgiveness and a promise of safe passage so that he could return to Derry. This was nine years after the Good Friday agreement had brought the conflict largely to an end, yet the Sinn Féin leader and former IRA man Martin McGuinness would say only that Gilmour would have to decide for himself whether or not it was safe to return.

Wisely, perhaps, Gilmour decided it was not. In October 2016 he died, aged 57, alone and an alcoholic, at his flat in a town on the south coast of England. His body lay undiscovered for so long that it had started to decompose by the time it was discovered. When one of Gilmour’s sons, Raymond Jr, heard the news, he posted on social media: “There is a God. Lol.”

In 1989, two masked men burst into the home of Pat Finucane, a Belfast solicitor, and shot him three times in the torso, three times in the neck and six times in the head. His wife and three young children were watching.

Many of Finucane’s clients were republicans; some were loyalists. He had become increasingly effective as an advocate, not only defending these clients before the criminal courts in Northern Ireland, but also challenging the security forces in the European courts. A number of his relatives were in the IRA.

As a consequence of his effectiveness and his family connections, Finucane was targeted by a loyalist who was on the Ministry of Defence payroll as an agent for military intelligence. The man who supplied the weapons to the loyalist gunmen who carried out the killing had been a Special Branch informer for 18 months. And when the getaway driver was arrested and confessed, he too was recruited as a tout, and the case against him was subsequently dropped.

Finucane’s murder was only the most glaring example of how the British state became entangled in the violence of its informers. Some agents became involved in very serious crimes while assisting the army and police. Others were recruited while being investigated for serious crimes.

One of Gary Haggarty’s associates in the UVF, a man called Mark Haddock, was also an informer. In her 2007 report on the UVF, the police ombudsman for Northern Ireland, Nuala O’Loan, reported that 14 years earlier, Special Branch had given Haddock a pay rise after he allegedly confessed to blasting a 27-year-old woman, Sharon McKenna, in the head with a shotgun. There were even allegations that his police handlers had paid for him to have a foreign holiday; the killing had consolidated Haddock’s position within the UVF, making him an even more useful tout. This was not an isolated crime: Haddock has been named in the Irish parliament, the Dáil, as being involved in the murder of McKenna and eight other people.

In January this year – a day after Haggarty’s sentencing – police arrested another alleged former informer, Freddie Scappaticci. A veteran IRA man in his early 70s, Scap, as he is widely known, allegedly commanded the IRA’s internal security unit, the so-called Nutting Squad. This unit was responsible for identifying and interrogating suspected touts, sometimes torturing them. Those thought to be guilty were executed, usually by being “nutted” – shot in the head. Throughout this time, Scap was also said to have worked for military intelligence, under the codename “Stakeknife”. A few years ago a former commander of the British army in Northern Ireland described him as “our best agent … the golden egg”.

But today, Britain’s handling of this supposed golden egg raises a number of troubling ethical questions about how informers were used. There is a current police investigation, led by senior detectives from England, into alleged murders by Scappaticci, as well as litigation against the police and the MoD, on behalf of a number of relatives of people allegedly killed by Scappaticci. Both aim to determine if British military intelligence – or their political masters – helped to decide who was condemned to death at the hands of the IRA’s Nutting Squad.

There were guidelines for the agent-runners who were handling people such as Scap and Haggarty, but they were based on a UK-wide protocol for dealing with ordinary crime that had been written before the conflict began, and were regarded as totally unworkable during the Troubles.

In 1989, an MI5 legal adviser warned the attorney general that the fundamental problem with the guidelines was that “in order to run a terrorist agent so as to gather intelligence or evidence, they must be continually breached”. The previous year, an RUC assistant chief constable had explained the problem clearly in a submission to British government officials in Belfast: if an informer told his handler that he had been asked to hide ammunition, for example, the handler could never offer satisfactory instructions. If he told the informer to go ahead and hide the ammunition, he would be breaching the guidelines, and probably the law. On the other hand, “if he directs the informer to refuse to comply, the latter will automatically become the subject of suspicion (and probable eventual death)”.

There is evidence that senior RUC Special Branch officers asked repeatedly that their agent-running operations be placed on a legislative basis, through an act of parliament, but successive British governments failed to do this until the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act came into force, just as the violence in Northern Ireland was coming largely to an end. At one point in the late 80s, for example, the head of Special Branch, Raymond White, made a personal plea to Thatcher for more definitive rules. According to an official investigation into Finucane’s murder, government officials advised White that the issue was “too difficult to handle”; he and his colleagues should carry on as before, and keep the details to themselves.

As a consequence of the way they allowed informers to continue operating, Special Branch, military intelligence and MI5 are today facing accusations that they colluded in killings. And such collusion did sometimes happen: there is good reason to believe that some police and intelligence officers used their informers to direct terrorists against chosen targets; that they began pulling the strings of the men who were pulling the triggers.

In apologising for what he described as “shocking levels of collusion” in the murder of Finucane, for example, David Cameron, as prime minister, admitted that “on the balance of probability”, a police officer or officers suggested to loyalist gunmen that the solicitor should be murdered.

Johnston Brown, a former RUC CID detective sergeant, wrote in his memoir about the Troubles: “I knew for a fact that the Special Branch was not averse to using their agents to target other terrorists. This was an acknowledged policy of theirs, whether official or not.”

But there is a bitter dispute about exactly what happened, and why. This is hardly surprising: there is a greater degree of peace in Northern Ireland than in the recent past, but little reconciliation, and the two communities are still fighting over that past. There are two different interpretations of recent history, disputes about the rights and wrongs of the conflict, and arguments about who should be applauded and who should be blamed.

There is no agreement on the causes of events, or even the language that should be used to describe them. Was the conflict a civil war or a series of crimes? Even the meaning of the word “collusion” is contested.

Former Special Branch officers believe that the word is now being wielded by republicans and their allies as a weapon in a battle to rewrite the past, as part of an effort to create a narrative in which all those involved in the conflict can be regarded as morally equivalent combatants, rather than as terrorists and police officers.

They are enraged by this, not just because they were law officers dealing with people who were breaking the law, but because the police killed just 1.4% – or 51 – of the 3,720 people who lost their lives during the Troubles, while the IRA and other republican groups killed around 58%. Furthermore, they say, they were trying to grapple with a seemingly intractable crisis that had dragged on for decades and was costing thousands of lives.

Unsurprisingly, republicans don’t see it that way. One former senior IRA man once told me of a conversation he had with a retired police officer, who was aghast at the suggestion that there could be some sort of moral equivalence between them. “I told him I agreed that there was no moral equivalence. Because I wasn’t being paid.”

After Haggarty joined the UVF as a 19-year-old in 1991, his new comrades in arms nicknamed him “Cowhead”. By all accounts a reserved and slightly humourless man, he rose through the ranks and became an area commander in 2004. He had been recruited as an informer as early as 1993, however, and was still being run by Special Branch 14 years later.

He was arrested in 2009, initially for questioning about the murder of Harbinson, and early the following year he agreed to become an “assisting offender” under the terms of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act. Under these terms, he was obliged to confess to everything he had done, and give evidence as a supergrass against any associates facing prosecution. The police who interviewed Haggarty as an assisting offender soon found he was no fool, and had an exceptional memory.

But during the years that Haggarty operated as an informer, did the value of the intelligence that he (and others like him) brought to Special Branch outweigh the misery and mayhem that he caused? In other words, did the informer system work?

The judge who sentenced Haggarty said he had provided the police with 300 pieces of intelligence, prevented 44 crimes from taking place – including murders, bombings, stabbings and arson – and warned his handlers about 34 people who were under threat from the UVF. He had also provided information about weapons and explosives, recruiting, targeting and drug offences. He is also said to have used his employment as a tyre fitter to give Special Branch the opportunity to bug people’s cars. Against this must be weighed the crimes Haggarty committed, the lives that he took, the lives that he ruined.

In a book published in 2016, a former Special Branch officer, William Matchett, assessed that around 20% of intelligence gathered during the Troubles came from technical eavesdropping, 15% from surveillance and around 5% from police and army patrols and open sources. The remaining 60%, he says, came from informers. And while some of the intelligence was undoubtedly low grade, some was not. Matchett argues that informers were the decisive factor in the intelligence war.

While only a tiny proportion of agents in Northern Ireland were fully fledged members of the IRA, Matchett says his fellow former officers estimate that each of these agents prevented around 37 killings each year, and that the total number of lives saved throughout the Troubles ran to many thousands. But, like everything else in Northern Ireland, these numbers will be accepted or rejected depending on one’s politics and one’s faith. As a loyalist gunrunner once told me, borrowing a few words from Simon and Garfunkel, this is still a place where “a man hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest”.

Weighing up the benefits of the intelligence that informers provided against the costs of the violent chaos that they unleashed is all but impossible. Can it be calculated on a crude, mathematical basis, counting the lives lost against the lives saved? How to factor in the disruptive impact of informers, and the way people may have left paramilitary organisations – or decided against joining – because they feared they would be exposed by a tout? How demoralising was it for paramilitary organisations to realise they had “a tout in the house” – that someone among their number was providing information to the enemy?

On the other hand, when an informer was able to kill and not face arrest, how often did his victim’s brothers or cousins or friends decide to take up arms to exact revenge? Did the crimes of informers exacerbate and prolong the conflict?

John Stevens told parliament that some of the 207 agents he arrested were working simultaneously for Special Branch, military intelligence and MI5, making handsome sums of money and frequently while fighting against each other, “which was all against the public interest and creating mayhem in Northern Ireland”.

Haggarty’s case underlines this point. Not only did he get away with murder because he was a police informer: it was because Haggarty was working for the police that he chose to kill Sean McParland. The court that sentenced him heard that the UVF commander in Mount Vernon, having resolved to murder McParland’s son-in-law, announced that he was going to flip a coin to decide which of his men would pull the trigger. Haggarty, sensing that he was under suspicion as a possible informer, told him to put the coin away: he would do the job.

As he came to the end of his sentencing remarks, the judge explained that Haggarty had not only been an informer, but since his arrest had become an assisting offender. This meant he was entitled to a discount on his sentence, as long as he had confessed to all his crimes – which he had, during 1,015 police interviews.

Haggarty received a life sentence for each murder, and his greatest tariff – the minimum term he must serve before being considered for release – was for the murder of Sean McParland. The judge set it at 35 years. But the judge then awarded Haggarty a 75% discount, which reduced the term to eight years and nine months. He was also entitled to a further 25% discount on this term, in acknowledgment of his guilty plea, reducing his sentence still further to just six-and-a-half years.

Anyone convicted of Troubles-related offences committed before the 1998 Good Friday agreement can apply for release after two years. And Haggarty’s most serious post-agreement offence – directing a terrorist organisation – was reduced by the discounting process from 25 years to four years and six months. As Haggarty had spent almost four years remanded in custody while being debriefed by police, he had effectively been sentenced to time served.

Before Haggarty was sentenced, the court heard he had given his Special Branch handlers advance notice of two UVF murders that they failed to prevent. On one occasion, the court heard, he was later told that police had followed the car carrying the killers, but lost sight of it. Those killers – who had been identified by Haggarty – went on to murder a young taxi driver, a father of two small children.

The police ombudsman, having investigated this, sent a file about Haggarty’s handlers to the director of public prosecutions, for him to decide if they should be prosecuted for a range of crimes, including conspiracy to murder.

In the event, the DPP decided that Haggarty lacked sufficient credibility, and plans for him to give evidence against a number of his former comrades in the UVF were abandoned. He is expected to give evidence against just one man, in a murder case in which there is alleged to be corroborating forensic evidence. In sentencing him, the judge acknowledged that “there is anger at the decision not to rely on Mr Haggarty’s evidence to prosecute individual police officers”, and added that the DPP had made clear that this did not mean Haggarty was disbelieved.

Among lawyers and journalists in Belfast, there is a widespread belief that prosecutors were reluctant to use Haggarty as a supergrass in trials of his old UVF comrades, because that would signal that he also possessed sufficient credibility to testify against his former police handlers. “It’s obvious,” says one leading local journalist. “It cries out at you.”

After Haggarty’s sentencing hearing in January, relatives of his victims who had attended the hearing went for a cup of tea at a cafe across the road from the court. Aaron McCone, whose father, John Harbinson, had been among those murdered, was joined by Ciaran Fox, whose father, Eamon, was murdered by Haggarty and others in May 1994, and Paul McKenna, whose sister Sharon was shot by Haggarty’s friend Mark Haddock a year before that.

They were all bitterly disappointed at the heavily discounted sentence, but not in the least surprised. “Nothing in court surprised us, but it’s still very hard to take,” said McCone, trying, and not quite succeeding, to hold back his tears. “He’s a serial killer and he’ll be out after serving a little over three years. That’s not justice.”

“We feel let down by the justice system in this country,” said Fox. “Gary Haggarty was allowed to kill at will. The police knew he was killing at will and they let him continue. If he had been a member of an Islamic terrorist organisation, he would be locked up for a very long time.”

As the three men spoke, a number of the CID detectives who had investigated Haggarty’s crimes, and who had interviewed him as an assisting offender, walked into the cafe. They saw the three men, turned on their heels and walked out. Paul shook his head. After Sharon was killed, he said, “the police only visited my family once”.

These men come from both of the communities in Northern Ireland, but none of them trust the police. In his book, Matchett writes that one of the purposes of recruiting agents was to unsettle members of paramilitary organisations; he calls them “force multipliers” that would induce paranoia in groups such as the IRA and the UVF. But the use of informers appears to have unsettled not only paramilitary organisations, but entire communities, particularly those neighbourhoods where these groups enjoyed support, or could at least rely on blind eyes being turned. In these places, people remain suspicious, untrusting of authority.

Ron Dudai, an Israeli criminologist who has closely studied the use of informers in Northern Ireland, describes it as “an open wound from the past” that continues to have a long-term effect. He believes that “informing has permeated many aspects of political and social life”, in a way that fuels suspicion of the police and is ultimately impeding the restoration of normality. Despite this, Dudai says, those involved in the peace process rarely discuss the use of informers.

Peace remains precarious in Northern Ireland. Punishment beatings and shootings of minor criminals are depressingly common in areas where paramilitary organisations traditionally held sway. European police forces reported that there were 142 failed, foiled or completed terrorist attacks across the continent in 2016. Seventy-six of them – more than half – were in Northern Ireland. In a place where bridges between police and communities still need to be built and maintained, many believe that the use of informers – and the granting of lenient punishments – can only damage public trust in law enforcement. “A perception that even convicted murderers are not seriously punished if they cut a deal with the police can affect the motivation of members of the public to contact the police with information about suspects, especially in communities where trust in the police and courts suffers from the legacy of the conflict,” says Dudai.

But new informers are still being recruited. Late last year, the courts in Northern Ireland heard complaints from two men who say police officers had made separate attempts to recruit them as touts – asking them to provide information on associates who are suspected terrorists. One, who has a recent conviction for firearms offences, said he had been approached three times by the same officers, twice while on holiday in Norway and then in Armagh, south of Belfast. These approaches, he complained, put his life at risk.

The second man, named in court only as “X”, said police threatened him last year, saying that if he did not agree to provide information, they would tell terrorism suspects that he already was an informer. An appeal court judge concluded that “there is a strong case that the police officer issued the threat” in his attempt to turn X into a tout. And so it goes on.