Every Monday afternoon, a steady stream of drug users at various stages of treatment gravitate to a cafe-style clinic based at a charity centre in Midlothian.

Sitting around a table with their teas and coffees, their chat encompasses anything from childhood memories to last night’s telly. There is an ongoing debate about whether Lidl or Aldi make better pop chips. Dogs are welcome.

“I overheard a lovely conversation the other week,” says Tracey Clusker, nurse manager for substance misuse at Midlothian health and social care partnership, and the driving force behind this ground-breaking approach to reaching some of Scotland’s most at-risk addicts.

“Someone was struggling with diazepam use, then someone else shared: ‘This is how I’ve coped’. There’s a real concern for one another, how they manage their addiction day to day. People who have gone into rehab still come in, so they see that people are getting well and there’s always that hope that things can change.”

While Tuesday’s shocking drug-related death figures, which put Scotland on a par with the US, have prompted calls for radical action, including decriminalisation, experts and frontline practitioners emphasise there is plenty to be done to save lives within the existing law.

Clusker’s cafe-clinic is almost unique in a treatment landscape dominated by what many consider an outdated and rigid medical model. There’s an open-door policy here; nobody is turned away, regardless of when they last used illegal drugs. And there’s a prescriber present, so if heroin users want to receive their opioid substitution treatment – usually methadone – here they can, with an initial prescription available within one week.

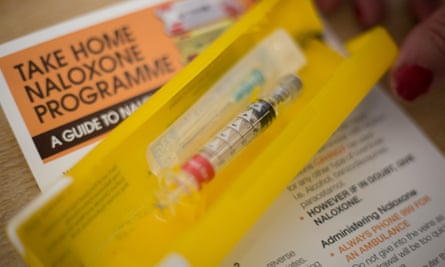

But there are also peer support workers to talk to, access to housing and benefits advice, mental health referrals, physical health checks, and a chance to pick up clean needles or overdose-reversing naloxone kits.

Clusker had the idea for this low-threshold drop-in clinic after clients told her about feeling judged in traditional healthcare settings, being discharged from treatment for missing appointments or failing urine tests, or being scared to attend if they were still using illegal drugs on top of their methadone.

“It’s about engagement and connection, and that’s just as important as the methadone or buprenorphine prescription,” she says.

Of the 1,187 drug-related deaths recorded in Scotland in 2018, 76% were individuals aged 35 and over. Like the regulars at Clusker’s cafe-clinic, they were mainly men, mainly heroin users, fitting the profile of the so-called Trainspotting generation of long-term, habitual drug takers who began using during the heroin epidemic of the 80s and early 90s and who were especially vulnerable to overdose as they encountered the unpredictably potent benzos that have flooded the UK market over the past few years.

With 15 years’ experience in the field, Clusker believes the key to keeping these people alive is to keep them in treatment, where they can receive a regular dose of a heroin substitute. This therapeutic dose must be high enough to sustain the individual – experts point to a culture of low dosing in many NHS services, with the unintended and dangerous consequence of self-medication with other drugs.

As the cafe-clinic celebrates its first birthday on Monday, it has increased attendance in this hardest-to-reach group from under 30% to more than 90%.

“This is really a clinic that’s treating trauma,” says Clusker. “What people are doing is using drugs as a solution to very difficult life experiences. I see a high proportion of looked-after children, or those affected by parental drug abuse, domestic violence, child sexual abuse. It’s also linked to poverty, austerity. There’s not many people at that clinic enjoying drug use. It’s not a choice.”

“We have patients who, as they get older, are very ambivalent about whether they are living or not,” says John Budd, a GP at the Edinburgh Access Practice and another local pioneer, who runs an innovative drop-in service for a similar cohort of homeless patients in the city centre. “They are continually defeated by the welfare system, by healthcare. They can’t wait the three-month average time it takes to get on to treatment. We have to work very hard to establish relationships with this group.”

Progress means meeting people on their terms, says Budd. He runs a regular pet clinic at the practice, which can give owners the opportunity to start a conversation about their own health needs, and offers outreach sessions at a nearby homeless crisis centre.

But how do the lessons of one innovative practice apply to an entire system? It is partly a question of resources, says Budd: drug and alcohol services are still recovering from a significant funding cut made by the Scottish government two years ago. “But there is a culture change needed. We put too many barriers in people’s way, while practitioners can still be risk-averse or lack training.”

The Scottish drug treatment system is “a black hole”, says Andrew McAuley, a senior research fellow at Glasgow Caledonian University. The highly respected health policy analyst, who has worked in the health service for 15 years, says: “The system is fragmented, under-resourced and is the same as it was 20 year ago, but people are using much more lethal poly-drug combinations now, with the rise of street benzos and injecting cocaine. They need the wraparound services because the cases are much more complex. But these are the things that get stripped out when funding becomes tight.”

McAuley contrasts what he sees as the current “political inertia” with Scotland’s world-leading approach to take-home naloxone – the antidote to opioid overdose – which was implemented nationally in 2011 and cited as an example of best practice by the World Health Organization.

Scotland’s public health minister, Joe Fitzpatrick, has committed to a public health approach to problem drug use in the wake of the latest fatality figures, having recently appointed a taskforce to consider international evidence around decriminalisation and drug consumption rooms, as well as investigating challenges around treatment services and stigma. But bereaved families want action.

“All everybody does is speak about it, what needs to be done, what they would like to do if they had the powers,” says Anne McDermott, whose son Scott died of a drug overdose in Edinburgh last year at the age of 35.

Scott was found to have six different drugs, including methadone, in his system when he died, and McDermott is perhaps understandably sceptical about the worth of substitution treatment alone.

She wants to see more rehab places, support for those trying to manage on methadone at home, and better use of drug treatment orders – a potentially life-saving community sanction that a recent freedom of information request from the Scottish Liberal Democrats found was used only 37 times in response to 3,600 convictions for possession in 2017-18.

McDermott believes that in big cities like Edinburgh, the public and the authorities have become inured to discarded needles, obviously intoxicated beggars and “just another junkie death”.

“They don’t ask the addicts what they need. They don’t ask those that would sell their soul for a bag, whose children are in care because drugs mean more.”