One hundred years ago – as dozens of state legislatures voted to ensure women across the country had the legal right to vote – South Carolina lawmakers said no.

It took almost 50 more years before the state officially ratified the 19th Amendment. About 30 years after that, 56% of the state’s registered voters were women.

The story of South Carolina’s women is one of slow progress, as Dr. Carol Sears Botch, a distinguished professor emerita at the University of South Carolina, puts it.

It’s a story that battled the idea of the Southern lady – a pedestal that did not include women of color or women without wealth, and a portrait of women as wives and mothers before anything else.

But it’s also a story of great resolve.

As part of a national project commemorating the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, this story spotlights 10 women from South Carolina who are part of a list of 510 American women from each state and the District of Columbia who've made a significant difference in the world.

To pick these Women of the Century, we took nominations from the public and then assembled an expert panel of historians, academics, journalists and women’s rights champions to consider those public nominations and brainstorm additional candidates.

We came up with a list of 55 incredible women from South Carolina who could not be stopped from breaking the cultural barriers that remained even as women became legally entitled to the same rights as men.

We discussed Shannon Faulkner’s fight for admission to the Citadel in 1995 and Nancy Mace’s graduation there in 1999 that pushed through one of the final establishments of all-male education in the state.

In the field of entertainment, we strongly considered Viola Davis, who was the first Black woman to be nominated three times for an Academy Award, and the first African American to win the "Triple Crown" of acting: An Academy Award, Emmy Award and Tony Award.

In the world of sports, there was Lillian Ellison, a trailblazer in the development of women's wrestling. And in politics, Liz Patterson came up as the first woman to represent South Carolina in Congress.

We also considered Julia Peterkin, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author whose works were unparalleled in her time in their portrayal of plantation life and the humanity of Black people, and Elizabeth Verner, South Carolina’s most notable female artist of the 20th century.

There were also three women close to making our final list that other states claimed for this project: Mary McLeod Bethune, a major influence on behalf of African American rights, is on Florida’s list; Marian Wright Edelman, one of the nation’s primary advocates for children’s rights and care, was included on the D.C. list; and Dawn Staley, a five-time WNBA All-Star with three consecutive Olympic gold medals, is on Virginia’s list.

But we had to narrow our list to just 10 women – a challenging task. Not every woman worthy of being celebrated made our final cut.

We looked specifically at women who lived in the 100 years since the 19th Amendment was passed (1920-2020). We also considered only women who had a documented track record of outstanding achievements, and we weighed how well known each woman was, how large of an impact she had and whether she was a U.S. citizen.

Ultimately, we chose the following 10 women. They represent just a sampling of the remarkable women in South Carolina’s history.

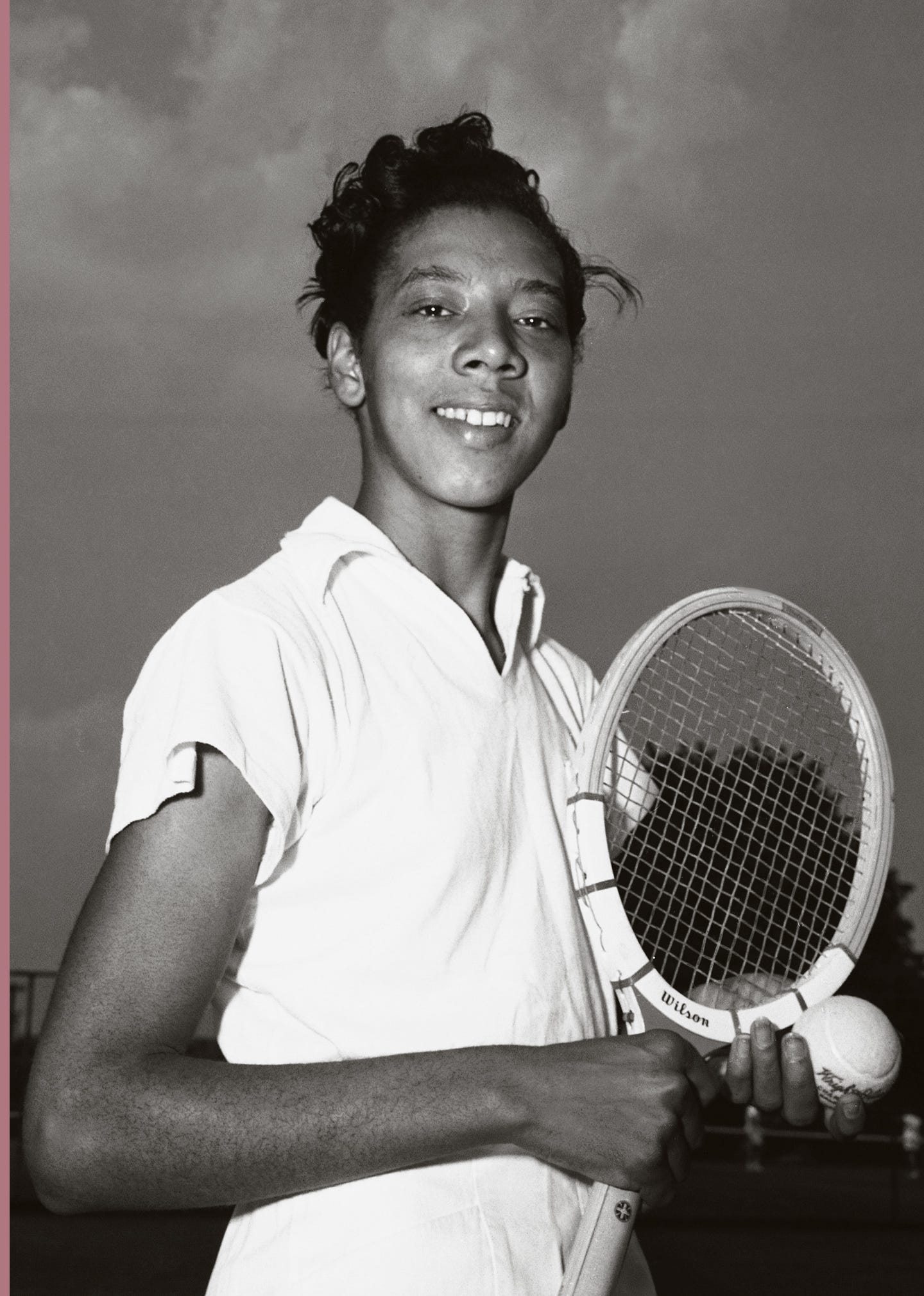

Althea Gibson

First African American to win a Grand Slam

(1927-2003)

The first person of color to win a Grand Slam title in tennis, Althea Gibson was born in rural Clarendon County, South Carolina, before moving to Harlem, New York, where she grew up.

Gibson was a trailblazer for athletes of color and especially women in the United States, changing hearts and minds about the importance of desegregation through her play on the tennis court at the onset of the Civil Rights movement. She broke the color barrier at the U.S. Open in 1950 as the first African American player to enter the competition.

Gibson went on to become America’s first Black Wimbledon champion in 1957 and repeated there again in 1958. She retired from professional play in 1958, finishing her career with 11 Grand Slam titles in both singles and doubles play. She was inducted into the U.S. Open Court of Champions in 2007.

Anita Pollitzer

Photographer and suffragist

(1894-1975)

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1894, Anita Pollitzer devoted her life to feminist politics, becoming a women’s rights advocate locally and nationally. A photographer and suffragist, Pollitzer went on to push for ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Pollitzer studied art at Columbia University and became close friends with Georgia O’Keefe. She introduced O’Keefe’s works to Alfred Stieglitz and wrote the defining book, “A Woman on Paper: Georgia O’Keefe,” which was released after Pollitzer’s death in 1975. Pollitzer accepted a position in the art department at the University of Virginia, but resigned to focus on the women’s rights movement. She later returned to earn a master’s degree in international law.

Pollitzer often visited home in South Carolina and, along with her sisters, founded the South Carolina branch of the Congressional Union, which later became part of the National Women’s Party. From 1945-49, she served as president of the National Women’s Party, the first group to picket for women’s rights. Arrested as a “Silent Sentinel” picketing the Woodrow Wilson White House in 1920, Pollitzer is credited with convincing Tennessee legislator Harry T. Burn to cast the deciding vote for the 19th Amendment.

Darla Moore

Investor and philanthropist

(1954- )

Born in 1954 in Lake City, South Carolina, Darla Moore made her way from her family’s tobacco, soybean and cotton farm all the way to Wall Street.

The University of South Carolina graduate was the vice president of Rainwater Inc., an investment company until 2012. Moore is also the founder and chair of the Palmetto Institute, a nonprofit thinktank that strives to raise income across South Carolina. In 1997, she was the first woman to be profiled on the cover of Fortune magazine and was named one of the Top 50 Most Powerful Women in American Business.

Moore has served on numerous corporate boards, including JP Morgan’s national advisory board. She has also served on the University of South Carolina’s board of trustees and the New York University Medical School and Hospital’s board of trustees.

Moore currently serves on the National Teach for America board of directors and the Culture Shed board. The University of South Carolina business school is named after Moore, the first business school in the country named for a woman. Recently, she’s moved back to Lake City part time.

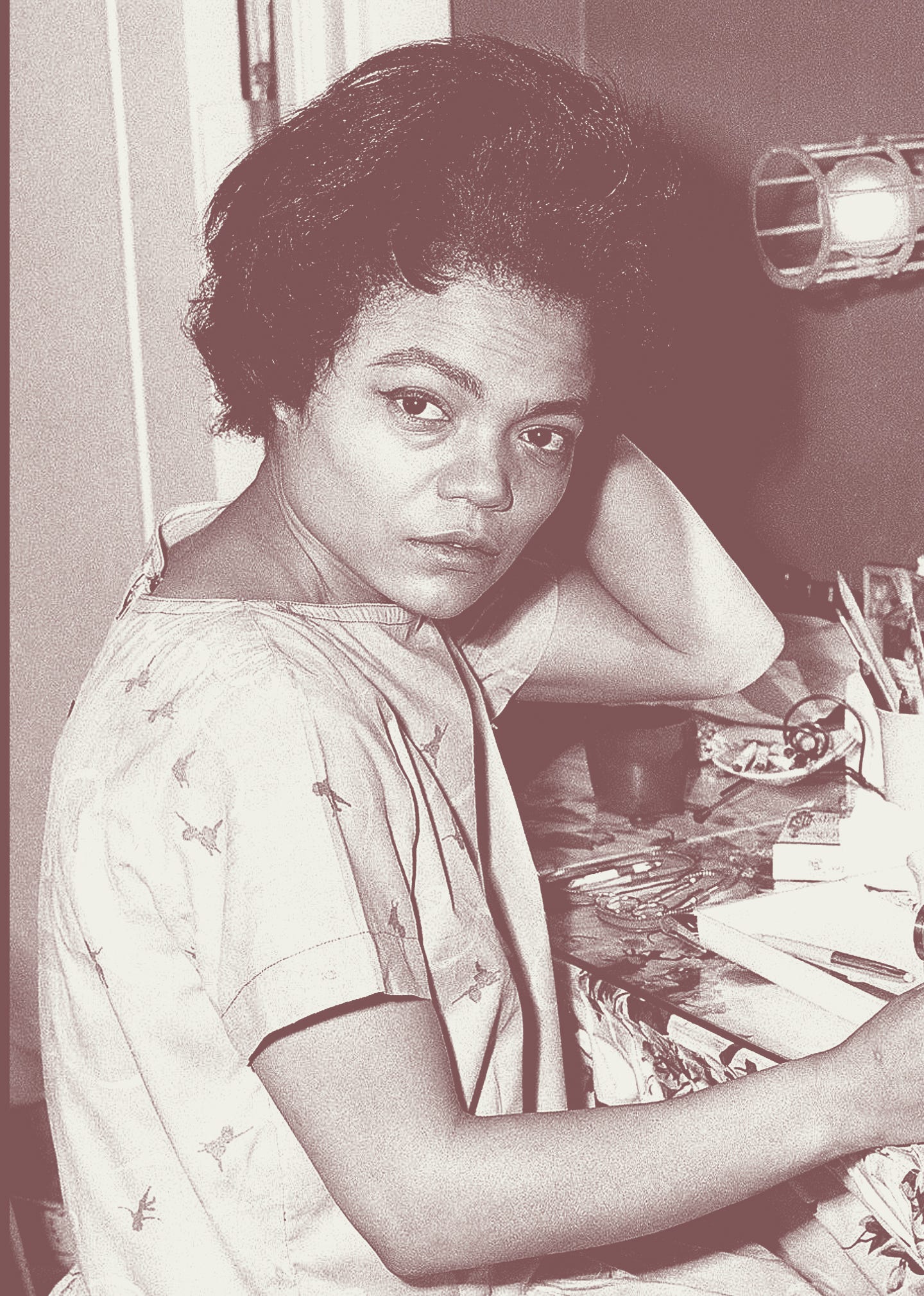

Eartha Kitt

Singer, actress, activist

(1927-2008)

Singer-actress Eartha Kitt left the South Carolina cotton fields and soared to international fame.

Most famous for her rendition of the song "Santa Baby" and the coquettish Catwoman on the "Batman" TV series in 1967 to 1968, Kitt was born in 1927 in St. Matthews, South Carolina, and spent her early childhood in North, South Carolina, before being sent to live with an aunt in New York at age 8.

Kitt's career began 1942 when, on a friend’s dare, she auditioned for the “Katherine Dunham Dance Troupe” and won a spot as a featured dancer and vocalist. She toured worldwide with the company before turning 20 and by 1945 was appearing on Broadway.

Throughout her career, Kitt found success in many fields. She acted in movies, playing opposite Nat King Cole in "St. Louis Blues" in 1958, and appearing in "Boomerang" and "Harriet the Spy" in the 1990s. Kitt, a Grammy-nominated singer, had hits in the U.S. and abroad. She earned several Emmy nominations, and Orson Welles called her “the most exciting woman in the world,” casting her as Helen of Troy in his production of “Dr. Faust.”

For all her fame, Kitt remained throughout her life a champion of the marginalized and oppressed.

Kitt was an outspoken supporter of HIV/AIDS organizations, often giving free benefit performances. She also supported efforts to prevent juvenile delinquency, forming a non-profit, the Kittsville Youth Foundation, and testified before a subcommittee of the House Committee on Education and Labor to help procure funds for “Rebels With A Cause,” a group bent on keeping youths out of trouble in Washington, D.C. Kitt was also a member of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and an outspoken critic of the Vietnam War, poverty and racial injustice.

Jean Hoefer Toal

First female chief justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court

(1943- )

Born in Columbia, Jean Hoefer Toal in 1988 became the first woman justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court. In 2000, Toal was named chief justice of the court, a role she held until she retired in 2015.

Toal was an attorney in South Carolina for 20 years before she was elected to the state’s Supreme Court. In 1975, Toal was elected to represent Richland County in the state House of Representatives, where she also became the first woman to chair a standing committee in the state’s House.

When Toal became a licensed attorney in 1968, she was one of the the fewer than 1 percent of licensed lawyers in the state who were women. In her career as an attorney, Toal represented a mix of plaintiffs and defendants in cases ranging from environmental law to criminal and civil matters.

Toal has received numerous awards for her work – from the Margaret Brent Women Lawyers of Achievement Award by the American Bar Association's Commission on Women, which is only given to five women in the United States per year, to the Sandra Day O'Connor Award for the Advancement of Civics Education by National Center for State Courts, of which Toal was the first recipient.

Matilda Evans

Health care advocate

(1872-1935)

Matilda Evans rose from a childhood picking cotton in South Carolina's rural Aiken County to making an immeasurable impact on health care access for African Americans in the post-Reconstruction era. The daughter of parents who were born into slavery, Evans took to heart their message that education was the way toward a brighter future, studying diligently to become a doctor. She earned her medical degree in 1897 from the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia, where she was the only African American student in her class.

Evans then returned to South Carolina, where she settled in Columbia, a city of about 25,000 people at the time, more than 40 percent of whom were African American. In doing so, she became the first Black woman native of South Carolina to work in the state as a physician.

After a successful period as a private practice physician for both Black and white patients, Evans gave up her business in 1901 to found the Taylor Lane Hospital and Training School for Nurses, the first hospital in Columbia open to African Americans. There she served as superintendent in a one-story wood frame building with room for 30 patients, offering free health care and health education. Evans went on to open a temporary free clinic for African Americans, which had such a high demand that it later became a permanent operation with financial backing from the State Board of Health and Richland County Legislative Delegation.

Through her career, Evans was known and respected for her work across segregated boundaries, giving her a platform to continue advocating for social and health care reform. Her influence on the rise of health care activism became a building block in the modern civil rights movement.

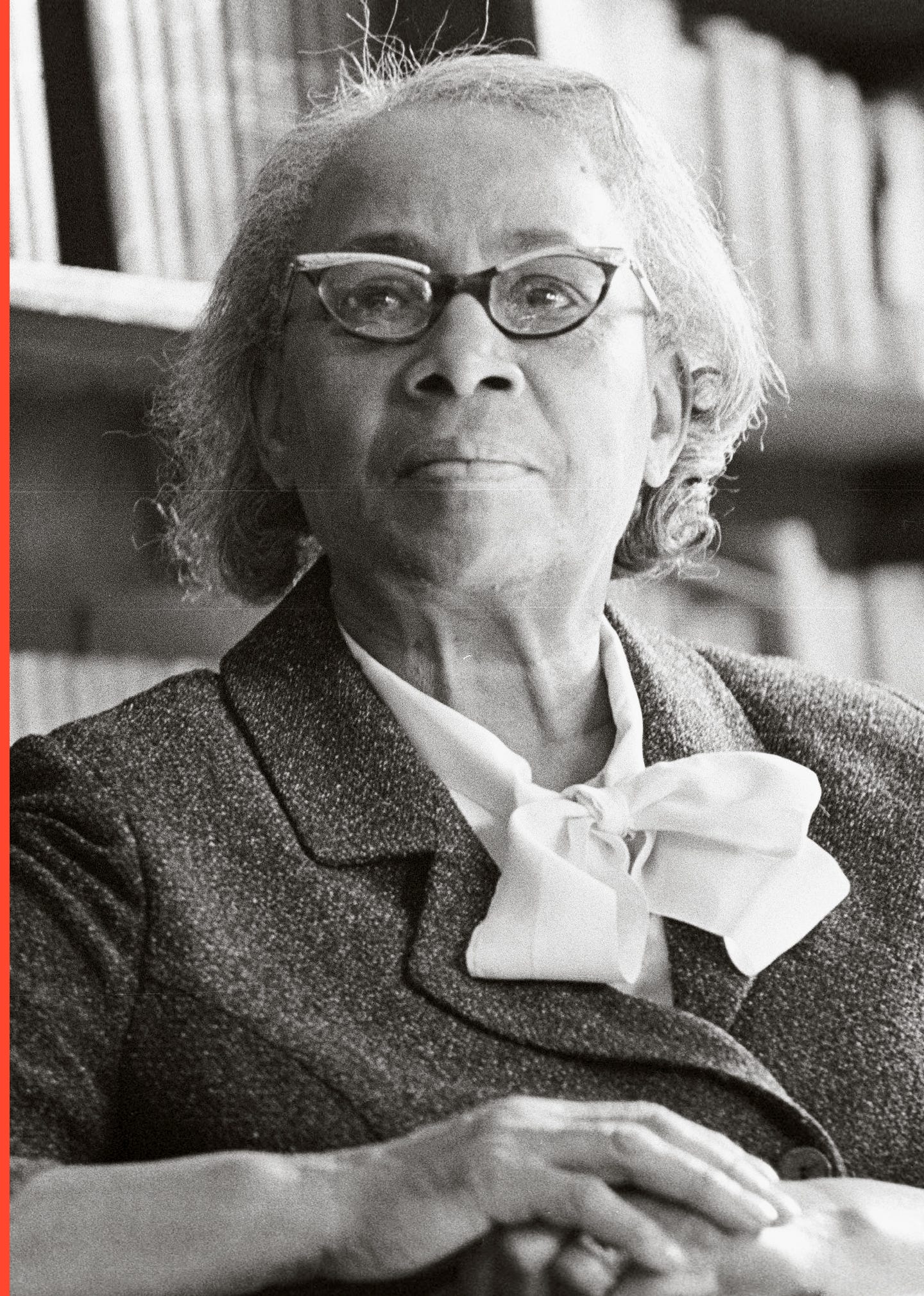

Modjeska Monteith Simkins

Public health worker and civil rights advocate

(1899-1992)

A public health worker and civil rights advocate, Columbia native Modjeska Monteith Simkins fought for racial equality at great personal cost.

Simkins’ parents instilled in their children a sense of civic duty and a desire to support their fellow African Americans.

She began attending Benedict College, then an institution for primary- through college-level students, in second grade and remained there through college. After college, Simkins became a teacher, but was forced to quit after getting married.

In 1931, Simkins went to work as Director of Negro Work for South Carolina Tuberculosis Association, but was fired a decade later for her work as a civil rights activist.

By then, she had become active with the NAACP, and was present at the founding of its South Carolina Conference. During her years with the NAACP, Simkins helped teachers in Columbia and Charleston fight for equal pay; she was also part of the Briggs vs. Elliott court case that sought to end desegregation in Clarendon County.

Her activism made her the target of violence, including shots being fired at her home, and being accused of subversive activities by the FBI and the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Simkins once said, “If the civil liberties of any person, whether a communist or a klansman, are trampled on … if I know a person has been mistreated, he’s my friend.”

She died in 1992 and posthumously received the South Carolina Order of the Palmetto, the state’s highest civilian award for service and achievements of national or statewide significance.

Nikki Haley

First female governor of South Carolina

(1972- )

Nikki Haley, a politician, businesswoman, diplomat and author, was South Carolina's first female governor and the first Indian American woman to serve as a governor in the United States.

Nimrata "Nikki" Randhawa Haley was born in Bamberg to parents who immigrated to the United States from India.

She served in the South Carolina House of Representatives from 2005 to 2011, representing District 87 in Lexington County, and was elected governor in 2010. Haley won her bid for reelection, serving as governor for six years before resigning to become U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.

While governor, Haley led the effort to remove the Confederate flag from South Carolina's Statehouse grounds in 2015 after white supremacist Dylann Roof fatally shot nine people at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston.

On Nov. 22, 2016, Haley became the first woman named to President-elect Donald Trump's administration. She announced in October 2018 that she would step down as U.N. ambassador.

Haley authored "With All Due Respect," a book about her experiences working for Trump. It was released in late 2019.

Septima Clark

Educator and civil rights activist known as the “Mother of the Movement”

(1898-1987)

Referred to as the “Mother of the Movement” for civil rights by Martin Luther King Jr., Septima Clark was born in Charleston to a laundrywoman and a former slave.

Clark started her teaching career in a one-room schoolhouse on Johns Island right after high school, during a time when the Charleston County school district did not hire Black teachers. Clark successfully petitioned for the district to change its policy.

Clark fought alongside the NAACP for integrated schools and equal pay for Black educators in South Carolina before she was fired by the Charleston district in the 1950s for her involvement in the movement. By 1976, the governor of South Carolina had declared her firing unjust. In 1979, she was given the Living Legacy Award by President Jimmy Carter.

Clark was perhaps most known for her “citizenship schools,” where she taught Black men and women to read so they could pass the literacy tests that often prevented generations of formerly enslaved families from voting.

Clark continued to advocate for the disenfranchised until her death.

Wil Lou Gray

Educator and adult literacy advocate

(1883-1984)

Education was the lifelong mission and passion of Laurens native Wil Lou Gray.

She began her teaching career in 1903 at the one-room Jones School in Greenwood. Seeing the levels of illiteracy and poverty among students and their families inspired Gray to focus on adult education.

In 1914, in an effort to help adults learn to read and write, Gray organized South Carolina’s first night school. Her efforts to lift adults of all races out of poverty led her to create four-week summer schools and adult educational camps.

In 1921, she founded the Wil Lou Gray Opportunity School, which still operates in West Columbia. The alternative-education school works with at-risk high-school-age students to help them develop leadership skills, achieve personal goals and earn a GED.

Gray received many accolades for her work, including the Algernon-Sidney Sullivan Award for service to mankind, the Service to the Black Race Award from South Carolina State University, and several honorary doctorates. She was inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame in 1974.

Gray retired in 1957 but continued to volunteer. She died at age 100, and her portrait hangs in the South Carolina State House.

Contributing: Greenville News reporters Angelia Davis, Gabe Cavallaro, Ariel Gilreath, Donna Walker and Genna Contino; digital director Catherine Rogers; and Beryl Dakers, executive director of cultural programming at SCETV.

Sources used in the Women of the Century list project include newspaper articles, state archives, historical websites, encyclopedias and other resources.