Advertisement

What A Boston Student's Deportation Reveals About School Police And Gang Intelligence

Resume

This story can also be read in Spanish.

It was a lunchtime argument among East Boston High School students that quickly fizzled. But what transpired that day set a series of actions in motion and, three years later, the repercussions are still unfolding for one young man named Orlando.

His story shows how observations of a seemingly-mundane high school argument can have a profound impact when placed in the hands of federal immigration officials.

'There's Too Much Death Here'

The small city of Metapán is about a two-hour drive from the Salvadoran capital of San Salvador. It's close to the border with Guatemala.

It's a hot and humid afternoon when we meet 22-year-old Orlando. He wipes sweat from his forehead every now and then and says it's safer for us to talk at the plaza instead of meeting him at his grandparents' house. He returned to El Salvador in January and says life is really hard here.

"I can't find a job here, there's nothing. It's really dangerous here," he says in Spanish. "There's too much death here. And fear — there's a lot of fear."

"I can't find a job here, there's nothing. It's really dangerous here. There's too much death here. And fear -- there's a lot of fear."

Orlando

We've agreed to use only his middle name because Orlando fears for his safety in El Salvador and for the safety of his grandparents. Orlando was born in Metapán, but it's never really felt like home. He says he was abandoned by his mother when he was younger and was more or less raising himself much of his life. That's why he decided to find his dad. When he was 17 he started the journey, alone, heading north toward the U.S.-Mexico border and, ultimately, East Boston.

"It was awful. I had to travel by land, and it was hard. There was a lot of suffering," he says. "I was mistreated a lot along the way."

Orlando says he was kidnapped in Mexico and held hostage for almost a month before he escaped. Soon after, he illegally crossed the border near McAllen, Texas.

He arrived as an unaccompanied minor in 2014 and was released to his father in Boston. Orlando obtained a special immigrant juvenile visa and applied for a green card. He says he felt safe in Boston, working and going to school.

"I don't know, I guess I got used to being with my family," he said. "That's what I wanted the most."

And then, in 2015, on a Thursday afternoon in November, all of that changed.

'It's A Black Box'

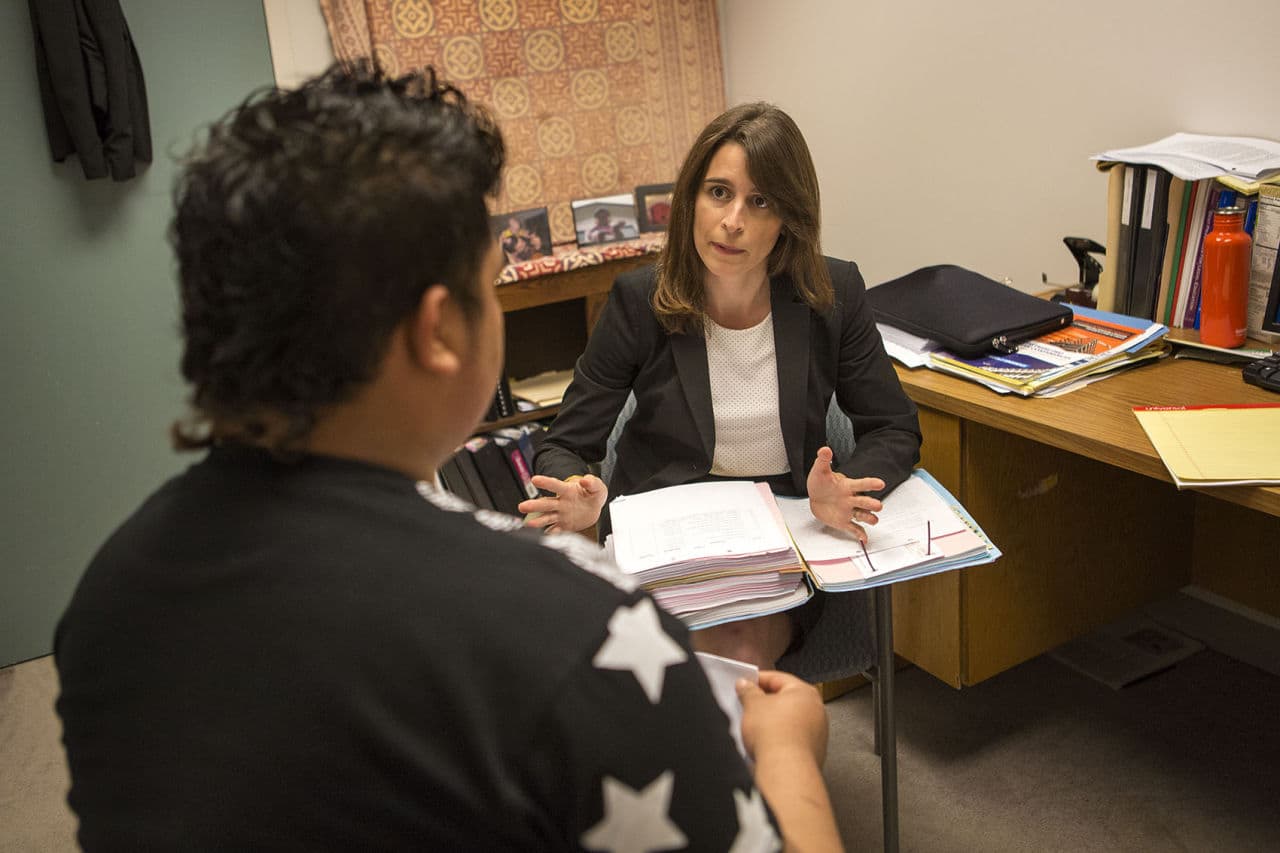

Attorney Sarah Sherman-Stokes opens the top drawer of a filing cabinet in her Boston University office. Sherman-Stokes is associate director at the university's Immigrants' Rights and Human Trafficking program. She represented Orlando in his immigration proceedings. She thumbs through dozens of folders, all related to Orlando's case.

"I mean, it does feel, in some ways, like this sort of tomb," she says, "where all the papers came to die."

Two of those pages — an incident report filed by an East Boston High School police officer — triggered what came next.

It started when a few students heckled another student in a classroom, the report details. The class dismisses and moves into the cafeteria for lunch, at which point a few students confront one another. What follows is described in the report as an "unsuccessful" attempt at starting a fight. One student is cited as telling a school official that he heard from friends that some of the young people involved might be part of a gang.

According to the report, school police officers reviewed security camera footage. Orlando was identified as one of the students involved. In the report, he's listed as an associate of the gang MS-13. The incident description ends, stating, "... this incident will also be sen[t] to the BRIC."

The Boston Regional Intelligence Center [BRIC] is a unit of the Boston Police Department that gathers and analyzes intelligence. That information is shared with federal law enforcement.

Nine months after the report was filed by the school police officer, Orlando was getting ready to go to work at a nearby Mexican restaurant when he was arrested at his father's home by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

That two-page school incident report had made its way into what's known as a "gang packet" — information compiled by Homeland Security Investigations, or HSI. It's unclear how, but Orlando allegedly evolved, in the eyes of authorities, into a verified and active member of MS-13. Those were the classifications printed in all capital letters on the first page of the government's gang packet.

"The maker of this report is usually a special agent from HSI and that person is usually not available in court to be cross-examined," said Sherman-Stokes. "One of the problems here is that it's a black box. You know, it's not clear to us how this determination that the client is a verified and active member of a street gang — how is that determination made?"

The government's case also included a few pictures printed from Orlando's Facebook account. Handwritten notes in the margins and arrows point to details like blue shoelaces and a Chicago Bulls hat as proof, prosecutors allege, of MS-13 affiliation.

Orlando, for his part, insists he was never involved with the gang. Orlando's lawyer, Sherman-Stokes, says he has no criminal record.

Around this time, East Boston and neighboring communities saw a spike in violent crimes believed to be associated with organized gang activity. Many of the victims were young men of Central American descent. In January 2016, federal, state and local law enforcement made arrests throughout Greater Boston that led to a sweeping indictment of more than 60 alleged MS-13 members and associates. Just last month, one of the members was sentenced to life in connection with the killings of two teenagers in East Boston. The victims had been stabbed dozens of times.

Orlando's school incident report was sent to the BRIC by a Boston School Police sergeant. According to a transcript of his immigration court testimony, the officer says he received no specialized training in identifying gang activity, but his years on the job taught him about gang behavior. He goes on to testify that tracking gang behavior is a big part of his duties at East Boston High.

School police officers are employees of Boston Public Schools, not the Boston Police Department. In an email, a Boston Public Schools spokesman said the Boston Police Department provides regular training to school police officers on gang activity.

'I Would Never Put This Into A Criminal Intelligence Database'

Thomas Nolan is a former Boston Police gang detective and a professor of criminology. He currently does work as an analyst, evaluating information for immigration attorneys whose clients have so-called "gang packets" created by the federal government.

Nolan says he's concerned Boston School Police officers are performing more like Boston police — but without the proper training.

"Boston School Police are putting in information into the BRIC database that's oftentimes not only inaccurate, but they're [also] exceeding the bounds of their authority," he said.

Nolan also worked for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the agency overseeing regional intelligence centers like the BRIC. He says he traveled around the country training law enforcement on the kind of information that should be shared in these databases. WBUR showed him the school incident report alleging Orlando's gang association and describing the incident in the cafeteria.

"Well, someone receiving this kind of information at the BRIC needs to make an assessment as to whether or not this is appropriately included in the criminal intelligence database," Nolan said, "and if this was something that I saw, I would never put this into a criminal intelligence database."

The Boston Police Department did not respond to requests for comment.

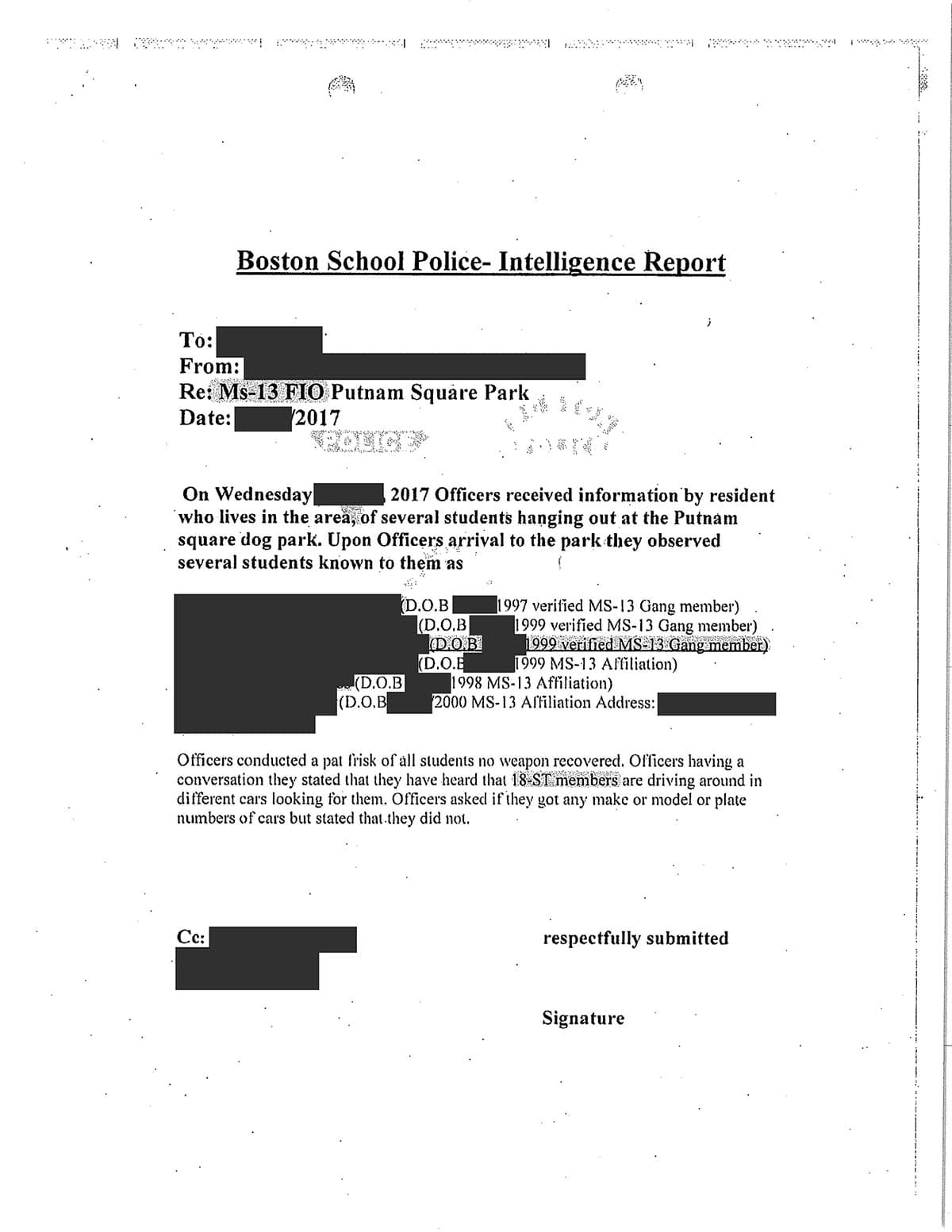

Some Boston School Police have exercised their authority off school property which, according to Boston Public Schools officials, is beyond school police jurisdiction. Six students listed in a "Boston School Police Intelligence Report" obtained by WBUR were stopped and frisked in 2017 by Boston School Police officers at a dog park in East Boston. The report was included in one of the federal government's "gang packets." It was filed by the same sergeant who alleged Orlando was a gang associate.

Nolan questions whether city leaders are fully aware of the way information flows between Boston School Police and federal immigration officials.

"This city, Boston, represents itself as a 'sanctuary city,' " he says. "It certainly conveys the idea that this city and its law enforcement agency will not cooperate and facilitate deportations and ICE detentions when, in fact, the Boston Regional Intelligence Center is doing just that."

WBUR submitted repeated public information requests to Boston Public Schools, asking for details about training for school police and other incident reports that include gang allegations. Despite winning an appeal from the state records office, WBUR received a response from the city denying the request and stating the records are part of active and ongoing litigation.

The ACLU of Massachusetts recently sued the Boston Police Department for access to its gang database, citing an uptick in allegations of gang membership being used to keep people in detention and, in some cases, as a basis for deportation.

Passing The Days

After spending more than a year detained in immigration custody in Boston, Orlando signed off on his own deportation in 2017, against the advice of his lawyer. He was too depressed, he says, to wait out the appeals process behind bars.

Sitting in Metapán, Orlando stares out into the plaza, reflecting on his life in Boston.

"I was there studying and working and everything. I was doing all that when they grabbed me," he says. "My life was ruined and truthfully, I don't know if I'm ever going to have another opportunity like that."

Orlando is still adjusting to his surroundings in El Salvador. He's looking for work, but says it's nearly impossible to find. He spends most days in the house, just sort of passing time.

This segment aired on December 12, 2018.