LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) -- Mary Jones drives Interstate 71 from her home in eastern Oldham County to her job in Louisville, a weekday commute she uses to listen to music and make phone calls.

And she’s spending more time on the road. A 17-mile trip that once took 20 minutes now usually lasts 35 minutes, she said, an increase she attributes to traffic from growth in Louisville’s outlying areas over the last 15 years.

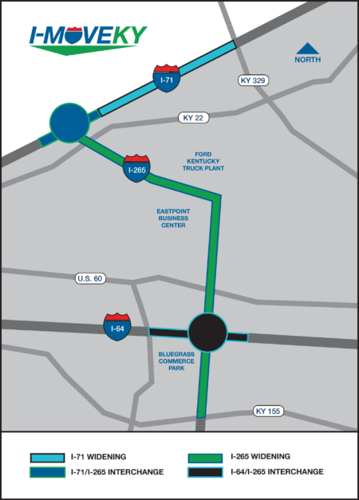

Aiming to ease congestion and boost safety, Kentucky plans to launch an ambitious highway expansion project later this year called I-Move Kentucky. It would add lanes to I-71 between the Gene Snyder Freeway and Ky. 329 near Crestwood, widen parts of the Snyder and rebuild ramps at the freeway’s interchange with I-64.

“It’s fantastic that there’s going to be some relief between Crestwood and the Snyder,” said Jones, a financial adviser who works on Brownsboro Road. “Because the Snyder certainly is the biggest bottleneck in the morning.”

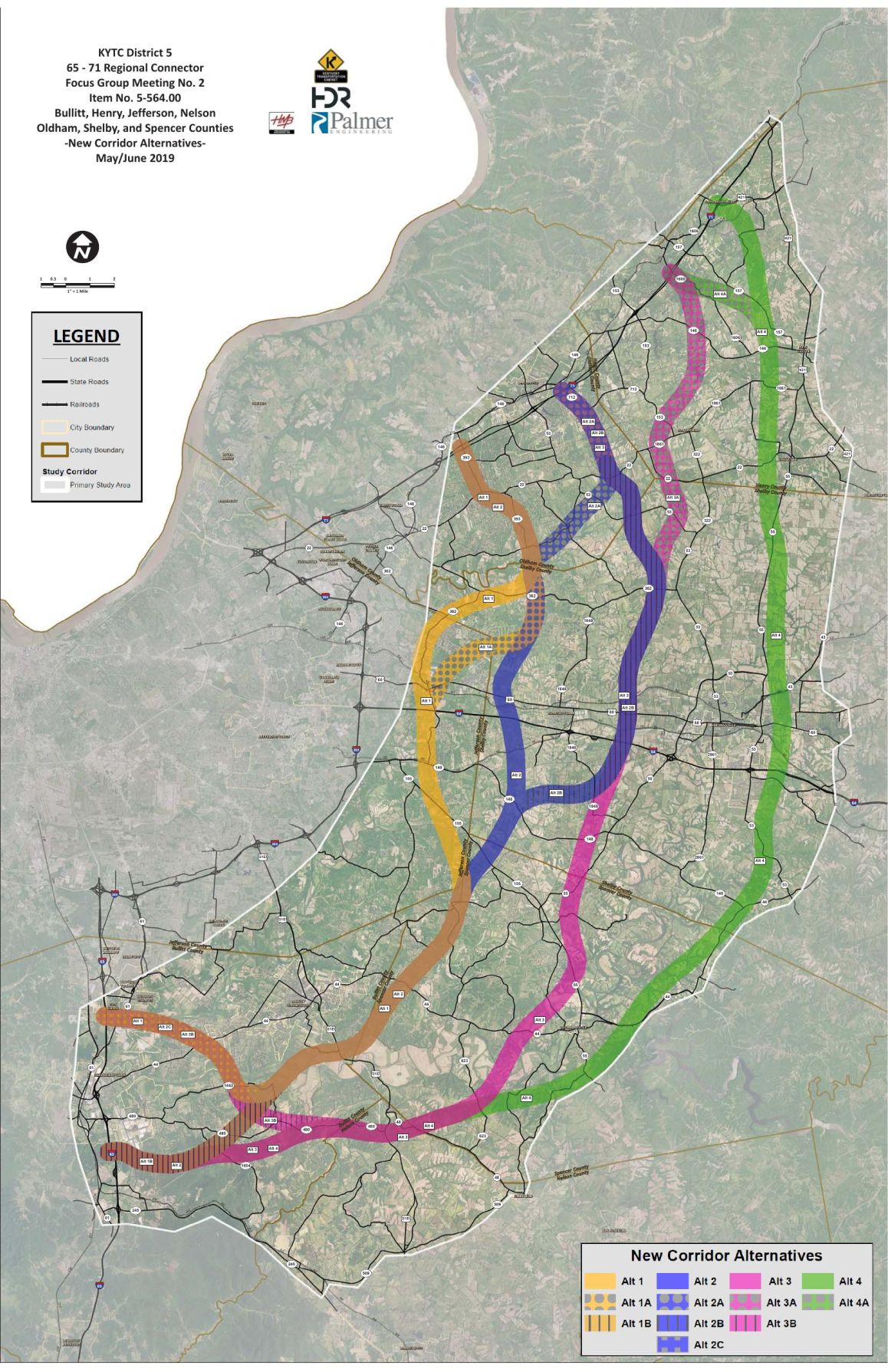

At the same time, the state is evaluating routes for another bypass around Louisville, including one corridor near eastern Jefferson County’s award-winning Floyds Fork parks system. Early cost estimates for the project, which has been likened to a new Snyder Freeway, range from $600 million to $1.6 billion.

But with Metro Louisville and Kentucky state governments facing financial challenges, those plans have ignited a debate about land use, transportation priorities and local-versus-state visions for Kentucky’s largest city and the surrounding region. The top elected leader in Bullitt County has questioned if a bypass is needed, and Mayor Greg Fischer’s administration also has expressed skepticism about the sprawling highway project.

A grassroots movement led by Bicycling for Louisville is urging the state to focus instead on projects inside the Watterson Expressway rather than the suburban-focused I-Move Kentucky and align their plans more with the city’s “Move Louisville” initiative.

Move Louisville, the Metro government plan that guides the city’s transportation planning for the decades to come, prioritizes several highway projects. But its main goals are “fixing and maintaining the existing infrastructure and reducing the number of miles that Louisvillians drive by providing and improving mobility options.”

Louisville also is working to curb its output of greenhouse gases, which are linked to climate change and largely the result of cars, trucks and other forms of transportation, according to federal data. The city’s goal is to cut emissions by 80 percent by 2050.

Maria Koetter, director of Metro government's Office of Sustainability, did not return a phone message for this story. Jean Porter, a Fischer spokeswoman, declined to say if the highway expansion projects make it harder for the city to attain the mayor’s goal of significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

But in a statement, Porter said there’s no conflict between I-Move Kentucky and the Move Louisville, noting that it also recommends state and federal spending on interstate improvements. The I-Move plan “does that,” she said.

“The state is helping us by investing $160 million of federal funds that the city is not otherwise eligible to use. The city remains committed to making multi-modal improvements to our transportation network and works closely with our partners … to fund those projects,” she said.

State officials argue that an expanded interstate network in the Louisville area is needed to make travel safer and faster and is based on data ranking the best use of transportation funds. At Gov. Matt Bevin’s direction, the Transportation Cabinet uses a formula that accounts for economic growth, safety and congestion, among other factors, in setting its funding goals.

Widening the Snyder from Taylorsville Road to Interstate 71 is Kentucky’s top priority, while widening I-71 ranks No. 11, according to the data.

The four projects in I-Move Kentucky

But critics say building more lanes is an outdated approach that may ease congestion for a few years but isn’t a wise investment for decades to come. They note research that suggests highway expansion actually leads to more traffic and voids any congestion relief within just a few years.

“The financial burden of building and maintaining roads is enormous,” said Jackie Cobb, a Louisvillian who believes the state should focus instead on roads that carry more than just automobiles.

“And then with our air quality issues – specifically, in Louisville, our air quality and carbon emission struggles -- I don’t see how road widening or building another bypass really helps with some of the explicitly stated goals of the city,” she said.

The Transportation Cabinet and its consultants aim to complete the bypass study by late fall, but any decision on whether to build a new road network linking I-71 and I-65 will need legislative approval.

Meanwhile, I-Move Kentucky is moving forward.

Kentucky plans to award a contract in October to design and build the extra interstate lanes and ramps. Teams led by Chicago-based Walsh Construction Co., which oversaw the work on the downtown part of the bridges project, and Louisville’s Hall Contracting of Kentucky are the two finalists.

In announcing I-Move Kentucky in April, Kentucky state highway engineer Andy Barber said the interstate expansion will give “motorists and businesses some of the same benefits that we got from the Ohio River Bridges Project: reduced congestion, increased safety and greater mobility that’s going to fuel economic development and quality of life in the greater Louisville region and throughout the Commonwealth.”

And Kentucky Transportation Cabinet Secretary Greg Thomas began making his case for the legislature to back the project earlier this month. State legislators, who will consider a two-year road spending plan when they convene in January, have set aside about $59 million of the roughly $180 million in estimated costs.

By using the “design-build” method that that lets a single company coordinate all aspects of construction, Thomas expects the state will save $11 million in maintenance spending that won’t be needed and reap other savings, including finishing the work by 2023 – three years faster than if the projects were done individually.

He told legislators on the Interim Joint Committee on Transportation that there were 918 crashes at the Snyder interchange with I-64 between 2015 and 2018. During the same period, Thomas said 360 wrecks happened in the I-71 stretch targeted by I-Move Kentucky.

“This project is important for safety as well,” he said.

State Rep. Maria Sorolis, a Democrat who represents eastern Jefferson County, said in an interview that while she's waiting for more information on the bypass proposal, I-Move Kentucky is needed now to improve congestion especially near the Snyder and I-64.

She also said the project is important to attracting new businesses.

"We have to be careful about living in a mindset that says, 'We can't, we cant, we can't,'" she said.

I-Move Kentucky is actually four projects:

• Widening the Gene Snyder Freeway between I-71 and Taylorsville Road and adding one lane in each direction toward the median of the current highway. The work would create six lanes in that section -- three lanes in each direction.

• Rebuilding the I-64 interchange at the Snyder. In May, state officials chose a design they claim will make spacing safer and more efficient and improve traffic flow “by the addition of lane capacity on four high volume ramps.”

• Widening I-71 toward the median between the Snyder and Ky. 329 by adding one lane in each direction, creating a total of six lanes.

• Building a “collector-distributor” lane on I-71 South at the Snyder. The goal is to improve safety and improve traffic flow.

The $91 million Snyder widening is the most expensive piece of I-Move Kentucky, according to state figures. But for the most part, a state study released in 2015 found that congestion isn’t a problem during the morning and afternoon rush-hour periods in the area set to be widened.

That study looked at traffic flow using a measure called “Level of Service,” which assigns an “A-F” rating based on congestion. A “D” rating is viewed as acceptable for urban areas.

In the Snyder corridor that’s part of I-Move Kentucky, only one of the eight sections studied had a rating worse than “D” during any of the peak travel periods: the part between I-64 and south of Shelbyville Road during the afternoon.

But by 2040, the study predicts, those ratings will deteriorate to “E” and “F” for all segments that would get an extra lane under I-Move Kentucky.

Yet adding lanes doesn’t mean an end to congestion, according to a traffic theory known as “induced demand.” It says that for a variety of reasons, including drivers who previously had avoided busy roads, new traffic will soon take up the extra capacity.

The Transportation Cabinet did not directly respond to a question about induced demand on the I-Move project, but spokeswoman Jordan Smith said in a statement that congestion will “worsen with time if left unaddressed. Looking ahead, traffic on these routes is projected to increase between 26% and 36% by 2045 as the greater Louisville region continues to grow, both commercially and residentially.”

The induced demand theory has critics who say those claims are overstated. Still, it’s been widely cited as a flaw in planning for new and expanded highways.

One study released this year found that the number of vehicle miles traveled in U.S. urban areas climbed in concert with added lane miles, with congestion relief from the new lanes disappearing within five years.

In other words: “If you build it they will come,” said Lynn Richards, president and CEO of the Congress for the New Urbanism, which held its annual meeting in Louisville last week.

“People will modify how they’re getting to work,” she said. “People will modify the times at which they will leave until the congestion comes right back up.”

Her organization advocates for well-designed cities that have many forms of transportation and other alternatives to the sprawling types of development, often driven by interstates, that occurred after World War II.

It’s that type of sprawl that some fear a new bypass could bring.

In 2018, the Kentucky legislature approved studying a connection between I-71 east of Louisville and I-65 in Bullitt County. A final report is due later this fall; researchers have identified 15 possible paths for the “regional connector,” including using existing roads.

Greater Louisville Inc. agrees that I-Move Kentucky is needed, but it’s waiting for more data on the bypass proposal, said Iris Wilbur, the regional chamber of commerce’s director of government affairs and public policy.

She said the chamber works with its members to weigh the potential benefits of a project, such as congestion relief, against unplanned effects like sprawl.

“We will be hypersensitive to any unintended consequences and assure that if we were to have some kind of specific position that we would account for that,” Wilbur said.

A regional bypass could pass through Spencer County

The Transportation Cabinet and consultant HDR Engineering are getting input from five focus groups on the bypass. The cabinet declined to provide names of the groups’ members when WDRB News asked on June 5, instead telling a reporter to file a request under the Kentucky Open Records Act.

The state has not yet responded to a request submitted on June 6, despite a requirement in the law that agencies must respond within three days.

The Fischer administration has taken part in the focus groups, said Mary Ellen Wiederwohl, chief of Louisville Forward, metro government's economic development agency. She said there are needs in the Louisville area, particularly in fast-growing Bullitt County.

At the same time, she said, Kentucky still has more road projects identified across the state than money available to pay for them.

“We’ve got to have a reality check as a city, a region and a state about projects that cost hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars, and we already have a road fund that is billions of dollars underfunded,” she said.

Reach reporter Marcus Green at 502-585-0825, mgreen@wdrb.com, on Twitter or on Facebook. Copyright 2019 WDRB Media. All rights reserved.